Uranus was hit by a massive object roughly twice the size of Earth that caused the planet to tilt during the formation of the solar system about four billion years ago. The „cataclysmic” collision shaped Uranus’ evolution – and could explain its freezing temperatures, according to a new study.

Astronomers from Durham University led an international team of experts to investigate how Uranus came to be tilted on its side and what consequences a giant impact would have had on the planet’s evolution. The team ran the first high-resolution computer simulations of different massive collisions with the ice giant to try to work out how the planet evolved.

The research confirms a previous study which said that Uranus’ tilted position was caused by a collision with a massive object – most likely a young proto-planet made of rock and ice. The simulations also suggested that debris from the impactor could form a thin shell near the edge of the planet’s ice layer and trap the heat emanating from Uranus’ core.

Scientists used a high-resolution simulation to confirm that an object twice the size of Earth collided with Uranus and altered its tilt.

The researchers said the trapping of the internal heat could in part help explain Uranus’ extremely cold temperature of the planet’s outer atmosphere minus 216 Celsius (-357 degrees Fahrenheit).

Study lead author Jacob Kegerreis, a PhD researcher in Durham University’s Institute for Computational Cosmology, said:

“Uranus spins on its side, with its axis pointing almost at right angles to those of all the other planets in the solar system. This was almost certainly caused by a giant impact, but we know very little about how this actually happened and how else such a violent event affected the planet. We ran more than 50 different impact scenarios using a high-powered super computer to see if we could recreate the conditions that shaped the planet’s evolution. Our findings confirm that the most likely outcome was that the young Uranus was involved in a cataclysmic collision with an object twice the mass of Earth, if not larger, knocking it on to its side and setting in process the events that helped create the planet we see today.”

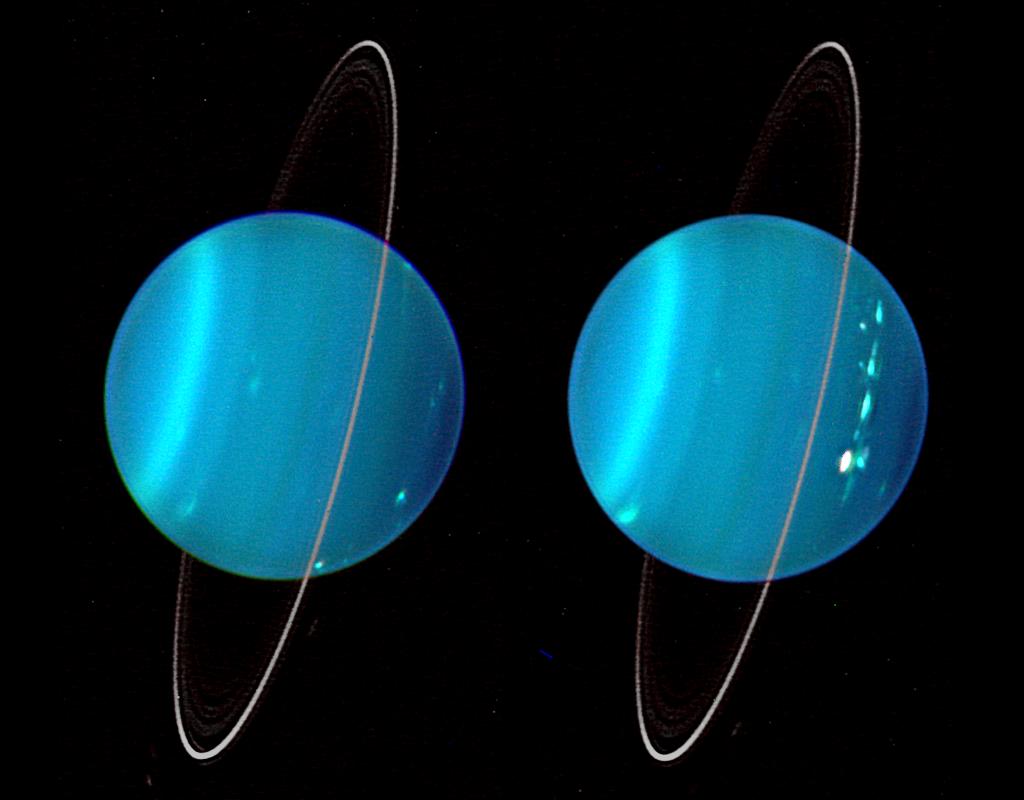

This composite image, created in 2004 with Keck Observatory telescope adaptive optics, shows Uranus’ two hemispheres.

There has been a question mark over how Uranus managed to retain its atmosphere when a violent collision might have been expected to send it hurtling into space. According to the simulations, this can most likely be explained by the impact object striking a grazing blow on the planet.

The collision was strong enough to affect Uranus’ tilt, but the planet was able to retain the majority of its atmosphere. The researchers say it could also help explain the formation of Uranus’ rings and moons, with the simulations suggesting the impact could jettison rock and ice into orbit around the planet. The rock and ice could have then clumped together to form the planet’s inner satellites and perhaps altered the rotation of any pre-existing moons already orbiting Uranus.

The simulations show that the impact could have created molten ice and lopsided lumps of rock inside the planet. This could help explain Uranus’ tilted and off-centre magnetic field. Uranus is similar to the most common type of exoplanets – planets found outside of our solar system – and the researchers hope their findings will help explain how such planets evolved and understand more about their chemical composition.

Co-author Dr Luis Teodoro, of the BAER/NASA Ames Research Centre, said:

“All the evidence points to giant impacts being frequent during planet formation, and with this kind of research we are now gaining more insight into their effect on potentially habitable exoplanets.”

The findings were published in The Astrophysical Journal.

În timpul formării sistemului solar, cu aproximativ patru miliarde de ani în urmă, Uranus a fost lovit de un obiect masiv de aproximativ două ori mai mare decât Pământul, ce a făcut ca planeta să se încline. Potrivit unui nou studiu, coliziunea „cataclismică” a remodelat revoluția lui Uranus în jurul axei sale, ceea ce ar putea explica temperaturile sale de îngheț.

Astronomii de la Universitatea Durham au condus o echipă internațională de experți pentru a investiga modul în care Uranus a ajuns să fie înclinat într-o parte și ce consecințe ar fi avut un impact gigantic asupra evoluției planetei. Echipa a efectuat primele simulări de calculator de înaltă rezoluție ale diferitelor coliziuni masive cu gigantul de gheață pentru a încerca să descopere modul în care a evoluat planeta.

Investigația confirmă un studiu anterior din care a rezultat că poziția înclinată a lui Uran a fost cauzată de o coliziune cu un obiect masiv – cel mai probabil o tânără proto-planetă din rocă și gheață. Simulările au sugerat, de asemenea, că resturile provenite din ciocnire ar putea forma o cochilie subțire în apropierea marginii stratului de gheață al planetei ce ar putea să capta căldura care provine din miezul lui Uranus.

Cercetătorii spun că izolarea căldurii interne ar putea ajuta, în parte, la explicarea temperaturii extrem de mici din atmosfera exterioară a planetei Uranus de minus 216 grade Celsius (-357 grade Fahrenheit).

Autorul principal al studiului, Jacob Kegerreis, doctorand la Institutul de Cosmologie Computatională din Durham, a declarat:

„Uranus se rotește cu axa orientată aproape în unghi drept față de cele ale celorlalte planete ale sistemului solar. Acest lucru a fost aproape sigur cauzat de un impact gigantic, dar știm foarte puțin despre cum s-a întâmplat acest lucru și cum acest eveniment violent a afectat planeta. Am rulat mai mult de 50 de scenarii diferite de impact folosind un super computer de mare putere pentru a vedea dacă am putea recrea condițiile care au modelat evoluția planetei. Constatările noastre confirmă faptul că cel mai probabil rezultat a fost faptul că tânărul Uranus a fost implicat într-o coliziune cataclismică cu un obiect de două ori masa Pământului, dacă nu chiar mai mare, care l-a lovit lateral declanșând evenimentele care au contribuit la crearea planetei pe care o vedem azi. ”

A existat un semn de întrebare asupra modului în care Uranus a reușit să-și păstreze atmosfera atunci când s-ar fi așteptat ca o ciocnire violentă să o trimită în spațiu. Conform simulărilor, acest lucru poate fi cel mai probabil explicat de obiectul a șters planeta precum ricoșeul unui glonte. Coliziunea a fost suficient de puternică pentru a afecta înclinarea lui Uranus, dar planeta a reușit să-și păstreze majoritatea atmosferei. Cercetătorii spun că ar putea explica, de asemenea, formarea inelelor și a lunilor, simulările sugerând că impactul ar putea arunca rocă și gheață în orbită în jurul planetei. Roca și gheața s-ar fi putut acumula împreună pentru a forma sateliții interiori ai planetei și, eventual, ar fi modificat rotația oricărei altei lune preexistente deja în orbita Uranus.

Simulările mai arată că impactul ar fi putut crea gheață topită și bulgări de stâncă în interiorul planetei. Acest lucru ar putea explica câmpul magnetic înclinat și în afara centrului lui Uranus. Uranus prezintă similitudini cu multe tipuri de exoplanete – planete găsite în afara sistemului nostru solar – și cercetătorii speră că descoperirile lor vor explica modul în care astfel de planete au evoluat și vor înțelege mai multe despre compoziția lor chimică.

Co-autorul Dr. Luis Teodoro, de la BAER / NASA Ames Research Center, a declarat:

„Toate dovezile indică faptul că impacturile gigantice sunt frecvente în timpul formării planetelor și, cu acest tip de cercetare, câștigăm acum o mai bună înțelegere a efectului lor asupra potențialelor exoplanete locuibile”.

Concluziile cercetărilor au fost publicate inițial în Jurnalul Astrofizic.

* „CE3K”- Close Encounters of the Third Kind- Întâlnire de gradul trei (ntr.)

***