When two black holes merge, they release a tremendous amount of energy. When LIGO detected the first black hole merger in 2015, we found that three solar masses worth of energy was released as gravitational waves. But gravitational waves don’t interact strongly with matter. The effects of gravitational waves are so small that you’d need to be extremely close to a merger to feel them. So how can we possibly observe the gravitational waves of merging black holes across millions of light-years?

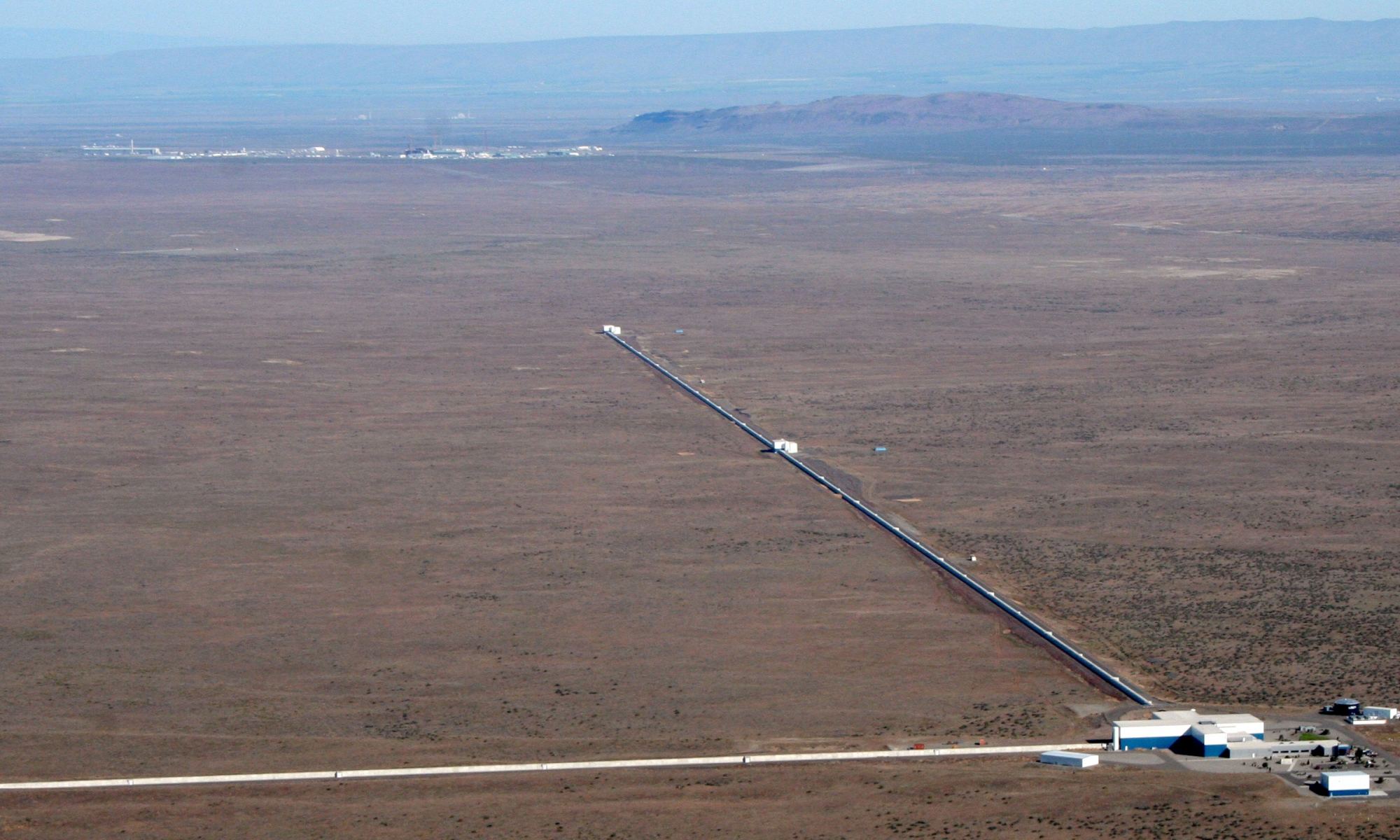

It’s ridiculously difficult. Gravitational waves are ripples in the structure of spacetime. When a gravitational wave passes through an object, the relative positions of the particles in the object shift slightly, and it’s only through those shifts that we can detect the gravitational waves. But that shift is minuscule. LIGO measures the shift by pairs of mirrors that are 4 kilometers apart. When a strong gravitational wave passes LIGO, the mirrors shift by only a few thousandths of the width of a proton.

LIGO measures this distance by a process known as laser interferometry. Light has wavelike properties, so when two beams of light overlap, they combine like waves. If the waves of the light line up, or are “in phase,” then they superpose to become brighter. If they are out of phase, they cancel out and become dimmer. So LIGO starts with a beam of light that in phase, and splits it, sending one beam along one arm of LIGO, and one along the other. The beams each bounce off a mirror 4 kilometers away, then return to combine into a single beam seen by a detector. If the distance of a mirror changes, so does the brightness of the combined light.

The wavelength of light is on the order of a micrometer, but gravitational waves only shift the mirrors by only a trillionth of that distance. So LIGO has each beam travel back and forth along an arm hundreds of times before they combine. This dramatically increases the sensitivity of LIGO, but it also raises other problems.

To work, the LIGO mirrors need to be isolated from any background vibrations from the ground and nearby instruments. To achieve this, the mirror arrays are suspended by thin threads of glass. The entire system also needs to be placed in a vacuum. The detector is so sensitive that air molecules passing through the light beams are picked up as noise. The air pressure inside LIGO‘s vacuum chamber is less than a trillionth of an atmosphere, which is lower than intergalactic space.

To the limits of human engineering, the LIGO system is an isolated vacuum system where the only thing that can move the mirrors is gravity itself. It isn’t perfect, but it is very good. So good that things start to get weird. Even if the detector was perfectly isolated, and placed in a perfect vacuum, the detectors would still pick up noise. The system is so sensitive that can pick up quantum fluctuations in empty space.

A central property of quantum systems is that they can never be completely pinned down. It’s part of Heisenberg’s Uncertainty Principle. This is true even for a vacuum. This means quantum fluctuations appear within the vacuum. As photons of light travel through these fluctuations, they are jostled a bit. This makes the beams of light move slightly out of phase. Imagine a fleet of small boats sailing across a rough sea, and how difficult it would be to keep them together.

But quantum uncertainty is a funny thing. Although aspects of a quantum system will always be uncertain, parts of it can be extremely precise. The catch is that if you make one part more precise another part becomes less precise. For light, this means you can keep the phase of the beam more aligned by making the brightness of the light more uncertain. This is known as squeezed light because you squeeze one uncertainty smaller at the cost of another.

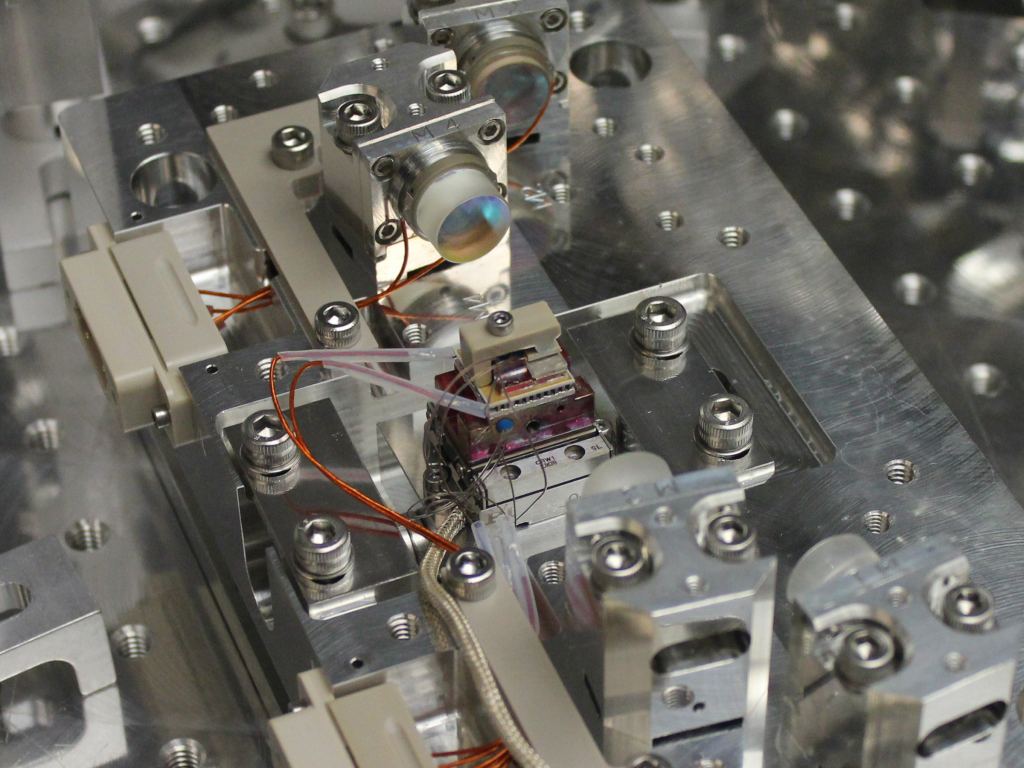

This squeezed state of light is done through an optical parametric oscillator. It’s basically a set of mirrors around a special kind of crystal. When the light passes through the crystal, it minimizes the fluctuations in phase. The fluctuations in amplitude get larger, but it’s the phase that matters most to the LIGO detectors.

With this upgrade, the sensitivity of LIGO should double. This will help astronomers see black hole mergers more clearly. It could also allow LIGO to see new kinds of mergers. Ones that are fainter or farther away than we’ve ever seen before.

Source: New Instrument extends LIGO’s reach, MIT News.

Când două găuri negre se contopesc, eliberează o cantitate extraordinară de energie. Când LIGO a detectat prima fuziune a unei găuri negre în 2015, am constatat că trei mase solare de energie au fost eliberate ca unde gravitaționale. Dar undele gravitaționale nu interacționează puternic cu materia. Efectele undelor gravitaționale sunt atât de mici încât trebuie să fii extrem de aproape de a le contopi pentru a le simți. Deci, cum putem observa, eventual, undele gravitaționale ale găurilor negre care fuzionează de-a lungul a milioane de ani-lumină?

Este aproape ridicol de dificil. Valurile gravitaționale sunt ondulări în structura spațiu-timpului. Când o undă gravitațională trece printr-un obiect, pozițiile relative ale particulelor din obiect se schimbă ușor și numai prin acele schimbări putem detecta undele gravitaționale. Dar această schimbare este minusculă. LIGO măsoară deplasarea cu perechi de oglinzi aflate la o distanță de 4 kilometri. Când o undă gravitațională puternică trece prin LIGO, oglinzile se deplasează doar cu câteva miimi din lățimea unui proton.

LIGO măsoară această distanță printr-un proces cunoscut sub numele de interferometrie laser. Lumina are proprietăți de undă, astfel încât atunci când două fascicule de lumină se suprapun, se combină ca undele. Dacă sunt „în fază”, atunci se supun pentru a deveni mai strălucitori. Dacă nu sunt în faza, anulează și devin dimmeri. Deci LIGO începe cu un fascicul de lumină care este în fază și îl împarte, trimițând un fascicul de-a lungul unui braț de LIGO și unul de-a lungul celuilalt. Fiecare se reflectă de pe o oglindă la 4 kilometri distanță, apoi se întoarce să se combine într-un singur fascicul văzut de un detector. Dacă distanța unei oglinzi se schimbă, la fel și strălucirea luminii combinate.

Lungimea de undă a luminii este de ordinul unui micrometru. LIGO are fiecare fascicul multiplicat de mai multe ori înainte de a se combina. Acest lucru crește dramatic sensibilitatea LIGO, dar ridică și alte probleme.

Pentru a funcționa, oglinzile LIGO trebuie izolate de vibrațiile de fundal de la sol și instrumentele din apropiere. Pentru a realiza acest lucru, tablourile de oglindă sunt suspendate de fire subțiri de sticlă. Întregul sistem trebuie de asemenea plasat în vid. Detectorul este atât de sensibil încât moleculele de aer care trec prin raze de lumină sunt preluate ca zgomot. Presiunea de aer din interiorul camerei de vid LIGO este mai mică de un trilion de atmosferă, care este mai mică decât în spațiul intergalactic.

Sistemul LIGO este un sistem de vid în care singurul lucru care poate mișca oglinzile este gravitația în sine. Nu este perfect, dar este foarte bun. Atât de bine încât lucrurile încep să devină ciudate. Chiar dacă detectorul ar fi perfect izolat, detectoarele vor amplifica zgomotul. Sistemul este atât de sensibil încât poate indica fluctuațiile cuantice din spațiul gol.

O proprietate centrală a sistemelor cuantice este aceea că ele nu pot fi niciodată fixate complet. Face parte din Principiul de incertitudine al lui Heisenberg. Acest lucru este valabil chiar și pentru vid. Aceasta înseamnă că fluctuațiile cuantice apar în vid. Pe măsură ce fotonii de lumină călătoresc prin aceste fluctuații. Este vorba despre fasciculele de lumină care se mișcă ușor și în fază. Imaginează-ți o flotă de bărci mici și cât de dificil ar fi să le ții împreună.

Dar incertitudinea cuantică este un lucru amuzant. Părțile acestuia pot fi extrem de precise. Captura este că dacă faceți una mai precisă, o altă parte devine mai puțin precisă. Pentru lumină, acest lucru înseamnă că puteți menține fasciculul de lumină în linie. Aceasta este cunoscută sub numele de o apăsare ușoară, deoarece stoarceți o incertitudine mai mică cu prețul alteia.

Această stare de lumină stoarsă se face printr-un oscilator parametric optic. Este practic un set de oglinzi în jurul unui tip special de cristal. Când lumina trece prin cristal, reduce la minimum fluctuațiile de fază. Fluctuațiile amplitudinii devin mai mari, dar faza este cea care contează cel mai mult pentru detectoarele LIGO.

Cu această actualizare, sensibilitatea LIGO ar trebui să se dubleze. Acest lucru îi va ajuta pe astronomi să vadă mai clar fuziunile găurilor negre. De asemenea, ar putea permite LIGO să vadă noi tipuri de fuziuni. Cele mai slabe sau mai departe decât am văzut până acum.

***