We can tell how much matter is in the universe by the motions of the stars. In the1920s, physicists attempting to do so discovered a discrepancy and concluded that there must be more matter in the universe than is detectable. How can this be?

In 1933, Swiss astronomer Fritz Zwicky, while observing the motion of galaxies in the Coma Cluster, began wondering what kept them together. There wasn’t enough mass to keep the galaxies from flying apart. Zwicky proposed that some kind of dark matter provided cohesion. But since he had no evidence, his theory was quickly dismissed.

Then, in 1968, astronomer Vera Rubin made a similar discovery. She was studying the Andromeda Galaxy at Kitt Peak Observatory in the mountains of southern Arizona when she came across something that puzzled her. Rubin was examining Andromeda’s rotation curve, or the speed at which the stars around the center rotate, and realized that the stars on the outer edges moved at the exact same rate as those at the interior, violating Newton’s laws of motion. This meant there was more matter in the galaxy than was detectable. Her punch card readouts are today considered the first evidence of the existence of dark matter.

Many other galaxies were studied throughout the ’70s. In each case, the same phenomenon was observed. Today, dark matter is thought to comprise up to 27% of the universe. „Normal” or baryonic matter makes up just 5%. That’s the stuff we can detect. Dark energy, which we can’t detect either, makes up 68%.

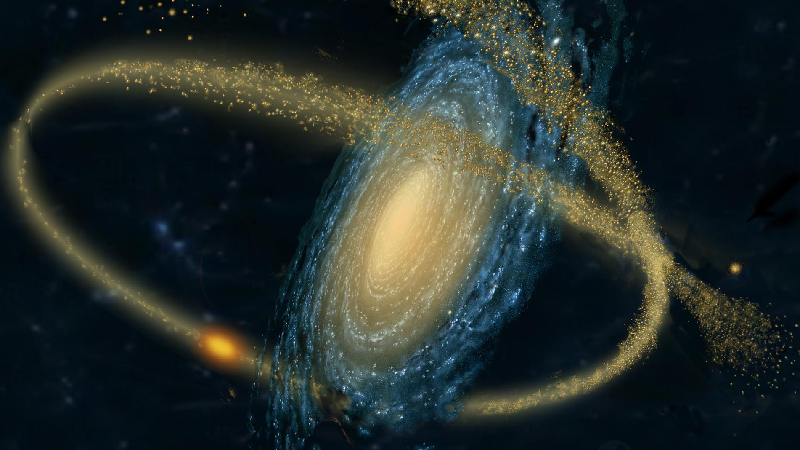

Dark energy is what accounts for the Hubble Constant, or the rate at which the universe is expanding. Dark matter on the other hand, affects how „normal” matter clumps together. It stabilizes galaxy clusters. It also affects the shape of galaxies, their rotation curves, and how stars move within them. Dark matter even affects how galaxies influence one another.

Leading theories on dark matter

NASA writes: ‘This graphic represents a slice of the spider-web-like structure of the universe, called the „cosmic web.” These great filaments are made largely of dark matter located in the space between galaxies.’Credit: NASA, ESA, and E. Hallman (University of Colorado, Boulder)

Since the ’70s, astronomers and physicists have been unable to identify any evidence of dark matter. One theory is it’s all tied up in space-bound objects calledMACHOs(Massive Compact Halo Objects). These include black holes, supermassive black holes,brown dwarfs, and neutron stars.

Another theory is that dark matter is made up of a type of non-baryonic matter, called WIMPS (Weakly Interacting Massive Particles). Baryonic matter is the kind made up of baryons, such as protons and neutrons and everything composed of them, which is anything with anatomic nucleus. Electrons, neutrinos, muons, and tau particles aren’t baryons, however, but a class of particles calledleptons. Even though the (hypothetical) WIMPS would have ten to a hundred times the mass of a proton, their interactions with normal matter would be weak, making them hard to detect.

Then there are those aforementioned neutrinos. Did you know that giant streams of them pass from the Sun through the Earth each day, without us ever noticing? They’re the focus of another theory that says that neutral neutrinos, that only interact with normal matter through gravity, are what dark matter is comprised of. Other candidates include two theoretical particles, the neutral axion and the uncharged photino.

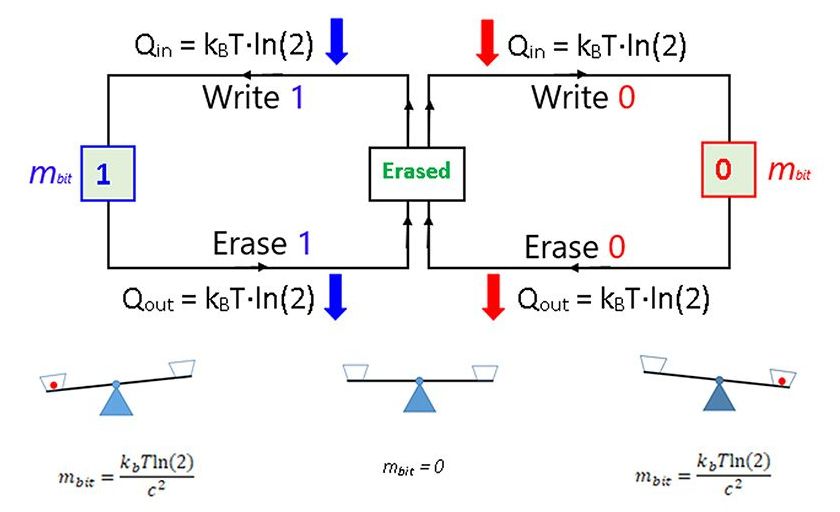

Now, one theoretical physicist posits an even more radical notion. What if dark matter didn’t exist at all? Dr. Melvin Vopson of the University of Portsmouth, in the UK, has a hypothesis he calls the mass-energy-information equivalence. It states that information is the fundamental building block of the universe, and it has mass. This accounts for the missing mass within galaxies, thus eliminating the hypothesis of dark matter entirely.

Information theory

To be clear, the idea that information is anessential building blockof the universe isn’t new. Classical Information Theory was first posited by Claude Elwood Shannon, the„father of the digital age”in the mid-20th century. The mathematician and engineer, well-known in scientific circles—but not so much outside of them, had a stroke of genius back in 1940. He realized that Boolean algebra coincided perfectly with telephone switching circuits. Soon, he proved that mathematics could be employed to design electrical systems.

Putem spune câtă materie este în univers studiind mișcările stelelor. În anii ’20, fizicienii care au încercat să facă acest lucru au descoperit o discrepanță și au ajuns la concluzia că trebuie să existe mai multă materie în univers decât este detectabilă. Cum poate fi aceasta?

În 1933, astronomul elvețian Fritz Zwicky, în timp ce observa mișcarea galaxiilor din Clusterul Coma, a început să se întrebe ce le ține împreună. Nu ar fi fost suficientă masă pentru a împiedica galaxiile să zboare. Zwicky a propus ca un fel de materie întunecată să ofere coeziune. Dar, din moment ce nu avea nicio dovadă, teoria lui a fost respinsă rapid.

Apoi, în 1968, astronomul Vera Rubin a făcut o descoperire similară. Ea studia Galaxia Andromeda de la Kitt Peak Observatory din munții din sudul Arizona, când a dat peste ceva care a nedumerit-o. Rubin examina curba de rotație a lui Andromeda sau viteza stelelelor în jurul centrului și își dă seama că stelele de pe marginile exterioare se deplasau exact cu aceeași viteză ca cele din interior, încălcând legile mișcării lui Newton. Aceasta însemna că în galaxie exista mai multă materie decât era detectabil. Însemnările făcute de ea sunt considerate astăzi prima dovadă a existenței materiei întunecate.

Multe alte galaxii au fost studiate de-a lungul anilor ’70. În fiecare caz, s-a observat același fenomen. Astăzi, se consideră că materia întunecată cuprinde până la 27% din univers. Materia „normală” sau baronică constituie doar 5%. Astea sunt lucrurile pe care le putem detecta. Energia întunecată, pe care nici nu o putem detecta, constituie 68%.

Energia întunecată este ceea ce reprezintă Constanta Hubble sau viteza cu care universul se extinde. Pe de altă parte, materia întunecată afectează modul în care materia „normală” se aglomerează. Stabilizează grupurile de galaxii. De asemenea, afectează forma galaxiilor, curbele lor de rotație și modul în care stelele se mișcă în interiorul lor. Materia întunecată afectează chiar modul în care galaxiile se influențează reciproc.

Multe alte galaxii au fost studiate de-a lungul anilor ’70. În fiecare caz, s-a observat același fenomen. Astăzi, se consideră că materia întunecată cuprinde până la 27% din univers. Materia „normală” sau baronică constituie doar 5%. Astea sunt lucrurile pe care le putem detecta. Energia întunecată, pe care nici nu o putem detecta, constituie 68%.

Energia întunecată este ceea ce reprezintă Constanta Hubble sau viteza cu care universul se extinde. Pe de altă parte, materia întunecată afectează modul în care materia „normală” se aglomerează. Stabilizează grupurile de galaxii. De asemenea, afectează forma galaxiilor, curbele lor de rotație și modul în care stelele se mișcă în interiorul lor. Materia întunecată afectează chiar modul în care galaxiile se influențează reciproc.

Teorii despre materia întunecată

Începând cu anii ’70, astronomii și fizicienii nu au putut identifica nicio dovadă de materie întunecată. O teorie este că totul este legat de obiecte legate de spațiu numite MACHO (Massive Compact Halo Objects). Acestea includ găurile negre, găurile negre supermasive, piticele brune și stelele cu neutroni.

The structure of dark matter in the Galaxy

O altă teorie este aceea că materia întunecată este alcătuită dintr-un tip de materie non-barionică, numită WIMPS (Particule masive care interacționează slab). Materia baronică este cea formată din barioni, cum ar fi protonii și neutronii și tot ceea ce este compus din aceștia, orice cu un nucleu atomic. Electronii, neutrinii, muonii și particulele tau nu sunt însă barioni, ci o clasă de particule numite leptoni. Chiar dacă WIMPS (ipotetic) ar avea de la zece până la o sută de ori masa unui proton, interacțiunile lor cu materia normală ar fi slabe, ceea ce le face greu de detectat.

Apoi există acei neutrini menționați mai sus. Știați că fluxuri uriașe din ei trec prin Soare și Pământ în fiecare zi, fără ca noi să ne dăm seama vreodată? Ei sunt în centrul atenției unei alte teorii care spune că neutrinii neutri, care interacționează doar cu materia normală prin gravitație, sunt cei din care se compune materia întunecată. Alți candidați includ două particule teoretice, neutral axion și uncharged photino.

Apoi există acei neutrini menționați mai sus. Știați că fluxuri uriașe din ei trec prin Soare și Pământ în fiecare zi, fără ca noi să ne dăm seama vreodată? Ei sunt în centrul atenției unei alte teorii care spune că neutrinii neutri, care interacționează doar cu materia normală prin gravitație, sunt cei din care se compune materia întunecată. Alți candidați includ două particule teoretice, neutral axion și uncharged photino.

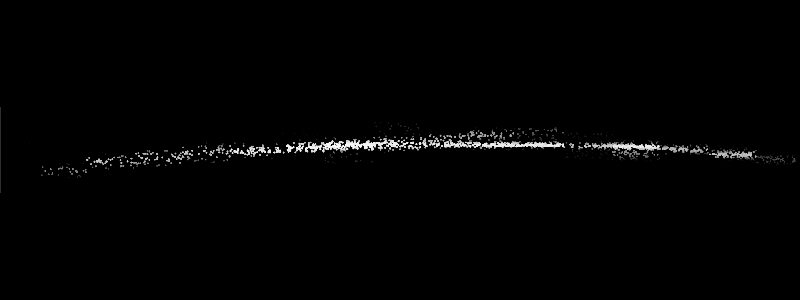

The detailed features of the GD-1 stream extracted from Gaia data allowed a new level of precision in simulating a stream-dark-matter encounter.

Acum, un fizician teoretician prezintă o noțiune și mai radicală. Ce se întâmplă dacă materia întunecată nu ar exista deloc? Dr. Melvin Vopson de la Universitatea Portsmouth, din Marea Britanie, are o ipoteză pe care o numește echivalența masă-energie-informație. Aceasta afirmă că informația este blocul fundamental al universului și are masă. Aceasta reprezintă masa care lipsește din galaxii, eliminând astfel în totalitate ipoteza materiei întunecate.

Pentru a fi clar, ideea că informația este un bloc esențial al universului nu este nouă. Teoria informațiilor clasice a fost prezentată pentru prima dată de Claude Elwood Shannon, „tatăl epocii digitale” la mijlocul secolului XX. Matematicianul și inginerul, binecunoscut în cercurile științifice a avut această idee de geniu în 1940. Și-a dat seama că algebra booleană coincidea perfect cu circuitele de comutare telefonică. Curând, el a dovedit că matematica poate fi folosită pentru proiectarea sistemelor electrice.

Va continua