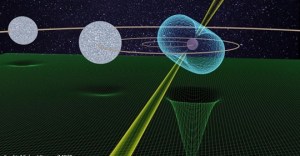

Once again, physicists have confirmed one of Albert Einstein’s core ideas about gravity — this time with the help of a neutron star flashing across space.The new work makes an old idea even more certain: that heavy and light objects fall at the same rate. Einstein wasn’t the first person to realize this; there are contested accounts of Galileo Galilei demonstrating the principle by dropping weights off the Tower of Pisa in the 16th century. And suggestions of the idea appear in the work of the 12th-century philosopher Abu’l-Barakāt al-Baghdādī. This concept eventually made its way into Isaac Newton’s model of physics, and then Einstein’s theory of general relativity as the gravitational „strong equivalence principle” (SEP). This new experiment demonstrates the truth of the SEP, using a falling neutron star, with more precision than ever.The SEP has appeared to be true for a long time. You might have seen this video of Apollo astronauts dropping a feather and a hammer in the vacuum of the moon, showing that they fall at the same rate in lunar gravity.https://www.youtube.com/embed/oYEgdZ3iEKABut small tests in the relatively weak gravitational fields of Earth, the moon or the sun don’t really put the SEP through its paces, according to Sharon Morsink, an astrophysicist at the University of Alberta in Canada, who wasn’t involved in the new study.”At some level, the majority of physicists believe that Einstein’s theory of gravity, called general relativity, is correct. However, that belief is mainly based on observations of phenomena taking place in regions of space with weak gravity, while Einstein’s theory of gravity is meant to explain phenomena taking place near really strong gravitational fields,” Morsink told Live Science. „Neutron stars and black holes are the objects that have the strongest known gravitational fields, so any test of gravity that involves these objects really test the heart of Einstein’s gravity theory.”Neutron stars are the collapsed cores of dead stars. Super dense, but not dense enough to form black holes, they can pack masses greater than that of our sun into whirling spheres just a few miles wide.The researchers focused on a type of neutron star called a pulsar, which from Earth’s perspective seems to flash as it spins. That flashing is a result of a bright spot on the star’s surface whirling in and out of view, 366 times per second. This spinning is regular enough to keep time by.Related:8 ways you can see Einstein’s theory of relativity in real lifeThis pulsar, known as J0337+1715, is special even among pulsars: It’s locked in a tight binary orbit with a white dwarf star. The two stars orbit each other as they circle a third star, also a white dwarf, just like Earth and the moon do as they circle the sun.(Researchers have already shown that the SEP is true for orbits like this in our solar system: Earth and the moon are affected to exactly the same degree by the sun’s gravity, measurements suggest.)The precise timekeeping of J0337+1715, combined with its relationship to those two gravity fields created by the two white dwarf stars, offers astronomers a unique opportunity to test the principle.The pulsar is much heavier than the other two stars in the system. But the pulsar still falls toward each of them a little bit as they fall toward the pulsar’s larger mass. (The same thing happens with you and Earth. When you jump, you fall back toward the planet very quickly. But the planet falls toward you as well — very slowly, due to your own low gravity, but at the exact same rate as a feather or a hammer would if you ignore air resistance.) And because J0337+1715 is such a precise timekeeper, astronomers on Earth can track how the gravitational fields of the two stars affect the pulsar’s period.To do so, the astronomers carefully timed the arrival of light from J0337+1715 using large radio telescopes, in particular the Nançay Radio Observatory in France. As the star moved around each of its neighbors — one in a quick little orbit and one in a longer, slower orbit — the pulsar got closer and farther from Earth. As the neutron star moved farther away from Earth, the light from its pulses had to travel longer distances to reach the telescope. So, to a tiny degree, the gaps between the pulses seemed to get longer.As the pulsar swung back toward Earth, the gaps between the pulses got shorter. That allowed physicists to build a robust model of the neutron star’s movement through space, explaining precisely how it interacted with the gravity fields of its neighbors. Their work built on a technique used in an earlier paper, published in the journal Nature in 2018, to study the same system.The new paper, published online June 10 in the journal Astronomy and Astrophysics, showed that the objects in this system behaved as Einstein’s theory predicts — or at least didn’t differ from Einstein’s predictions by more than 1.8 parts per million. That’s the absolute limit of the precision of their telescope data analysis. They reported 95% confidence in their findings.Morsink, who uses X-ray data to study the mass, widths, and surface patterns of neutron stars, said that this confirmation isn’t surprising, but it is important for her research.”In that work, we have to assume that Einstein’s theory of gravity is correct, since the data analysis is already very complex,” Morsink told Live Science in an in an email. „So tests of Einstein’s gravity using neutron stars really make me feel better about our assumption that Einstein’s theory describes the gravity of a neutron star correctly!”Without understanding the SEP, Einstein would never have been able to develop his ideas of relativity. In an insight he described as „the most fortunate thought in my life,” he recognized that objects in free fall don’t feel the gravitational fields tugging on them.(This is why astronauts in orbit around the Earth float. In constant free fall, they don’t experience the gravitational field that holds them in orbit. Without windows, they wouldn’t know Earth was there at all.)Most of Einstein’s key insights about the universe begin with the universality of free fall. So, in this way, the cornerstone of general relativity has been made that much stronger.

Încă o dată, fizicienii au confirmat una dintre ideile de bază ale lui Albert Einstein despre gravitație – de data aceasta cu ajutorul unei stele de neutroni. Se pleacă de la o constatare mai veche: că obiectele grele și ușoare cad în același ritm. Einstein nu a fost prima persoană care a realizat acest lucru; există relatări contestate despre Galileo Galilei, care demonstrează principiul, aruncând greutăți de pe Turnul Pisa în secolul al XVI-lea. Iar sugestiile ideii apar în opera filosofului din secolul al XII-lea Abu’l-Barakāt al-Baghdādī. Acest concept și-a făcut loc în cele din urmă în modelul de fizică al lui Isaac Newton și apoi în teoria relativității generale a lui Einstein ca „principiul echivalenței puternice” (SEP) gravitațional. Acest nou experiment demonstrează adevărul SEP, folosind o stea de neutroni în cădere, cu mai multă precizie ca oricând. SEP pare a fi adevărat de mult timp. S-ar putea să fi văzut acel videoclip al astronauților Apollo care aruncă o pană și un ciocan în vidul lunii, arătând că acestea cad în același ritm în gravitația lunară. câmpurile gravitaționale relativ slabe ale Pământului, lunii sau soarelui nu prea pot descrie SEP-ul, potrivit Sharon Morsink, astrofizician la Universitatea din Alberta din Canada, care nu a fost implicată în noul studiu. „La un anumit nivel, majoritatea fizicienilor consideră că teoria gravitației a lui Einstein, numită relativitatea generală, este corectă. Totuși, această credință se bazează în principal pe observațiile fenomenelor care au loc în regiuni ale spațiului cu gravitație slabă, în timp ce teoria gravitației a lui Einstein este menită pentru a explica fenomenele care au loc în apropierea câmpurilor gravitaționale foarte puternice „, a spus Morsink pentru Live Science. „Stelele neutronice și găurile negre sunt obiectele care au cele mai puternice câmpuri gravitaționale cunoscute, astfel încât orice test de gravitație care implică aceste obiecte poate verifica teoria gravitației lui Einstein.” Stelele neutronice sunt nucleele prăbușite ale stelelor moarte. Super dense, dar nu suficient pentru a forma găuri negre, pot concentra mase mai mari decât cea a soarelui nostru în diametri de doar câțiva kilometri . Cercetătorii au ales un tip de stea de neutroni numită pulsar, care din perspectiva Pământului pare să sclipește în timp ce se învârte. Acea clipire este rezultatul unui punct luminos de pe suprafața stelei care se învârte în interiorul și în afara vederii, de 366 de ori pe secundă. Această rotire este suficient de regulată pentru a păstra timpul. Acest pulsar, cunoscut sub numele de J0337 + 1715, este special chiar și în rândul pulsarilor: este blocat pe o orbită binară strânsă cu o stea pitică albă. . Cele două stele orbitează una pe cealaltă în timp ce înconjoară o a treia stea, de asemenea o pitică albă, la fel cum fac Pământul și luna în timp ce înconjoară soarele (cercetătorii au arătat deja că SEP este adevărat pentru orbite de acest fel în sistemul nostru solar: Pământul și luna sunt afectate exact în același grad de gravitația soarelui, sugerează măsurătorile.) Cronometrarea precisă a J0337 + 1715, combinată cu relația sa cu cele două câmpuri de gravitație create de cele două stele pitice albe, oferă astronomilor o oportunitate unică pentru a testa principiul. Pulsarul este mult mai greu decât celelalte două stele din sistem. Dar pulsarul cade încă spre fiecare dintre ei un pic în timp ce cad spre masa mai mare a pulsarului. (Același lucru se întâmplă cu tine și cu Pământul. Când sari, cazi înapoi către planetă foarte repede. Dar și planeta cade spre tine – foarte încet, datorită propriei tale gravitații reduse, dar cu exact aceeași viteză ca pene sau un ciocan ar fi dacă ignorați rezistența la aer.) Și pentru că J0337 + 1715 este un cronometru atât de precis, astronomii de pe Pământ pot urmări modul în care câmpurile gravitaționale ale celor două stele afectează perioada pulsarului. Pentru a face acest lucru, astronomii au cronometrat cu atenție sosirea luminii de la J0337 + 1715 folosind radiotelescoape mari, în special Observatorul Radio Nançay din Franța. Pe măsură ce steaua se deplasa în jurul fiecăruia dintre vecinii săi – una pe o orbită mică și una pe o orbită mai lungă și mai lentă – pulsarul s-a apropiat și depărtat de Pământ. Pe măsură ce steaua de neutroni s-a îndepărtat mai departe de Pământ, lumina din impulsurile sale a trebuit să parcurgă distanțe mai mari pentru a ajunge la telescop. Deci, într-o mică măsură, decalajele dintre impulsuri păreau să se lungească. Pe măsură ce pulsarul se învârtea înapoi spre Pământ, decalajele dintre impulsuri s-au redus. Acest lucru le-a permis fizicienilor să construiască un model robust al mișcării stelei de neutroni prin spațiu, explicând cu exactitate modul în care a interacționat cu câmpurile gravitaționale ale vecinilor săi. Munca lor s-a bazat pe o tehnică utilizată într-o lucrare anterioară, publicată în revista Nature în 2018, pentru a studia același sistem. Noua lucrare, publicată online pe 10 iunie în revista Astronomy and Astrophysics, a arătat că obiectele din acest sistem s-au comportat așa cum prezice Teoria lui Einstein – sau cel puțin nu diferă de predicțiile lui Einstein cu mai mult de 1,8 părți pe milion.

Aceasta este limita absolută a preciziei analizei datelor telescopului lor. Ei au raportat o precizie de 95% în constatările lor.

Morsink, care folosește date cu raze X pentru a studia masa, lățimile și modelele de suprafață ale stelelor de neutroni, a spus că această confirmare nu este surprinzătoare, dar este importantă pentru cercetările ei.

„În această lucrare, trebuie să presupunem că teoria gravitației lui Einstein este corectă, deoarece analiza datelor este deja foarte complexă”, a declarat Morsink pentru Live Science într-un e-mail. „Așadar, testele gravitației lui Einstein folosind stele de neutroni mă fac să mă simt mai bine în legătură cu presupunerea noastră că teoria lui Einstein descrie gravitația unei stele de neutroni în mod corect!” Fără să înțeleagă SEP, Einstein nu ar fi putut niciodată să-și dezvolte ideile relativității. Într-o perspectivă pe care a descris-o drept „cel mai norocos gând din viața mea”, a recunoscut că obiectele aflate în cădere liberă nu simt câmpurile gravitaționale care le trag de ele.

(Acesta este motivul pentru care astronauții pe orbită în jurul Pământului plutesc. În cădere liberă constantă, ei nu experimentează câmpul gravitațional care îi ține pe orbită. Fără ferestre, nu ar ști deloc că Pământul este acolo.)

Majoritatea perspectivelor cheie ale lui Einstein despre univers încep cu universalitatea căderii libere. Deci, în acest fel, piatra de temelie a relativității generale a fost încă odată demonstrată.