stă-n pat la televizor fuego rupe tăcerea o rupe felixcitări! tocmai ai salvat 0,02% dintr-un copac și 0,05% dintr-un tufiș! Tu ești salvarea Amazonului! senzațional! uluitor! incredibil! fenomenal! am descoperit o gură de cafea pe fundul unei căni urarea la mulți ani spusă pe tonul hai, că nu mai e mult momentul de grație întârzie […]

Arhive categorie:Fără categorie

Arhiva secretă de top a CIA: războiul SUA din Siria planificat din 1983 — Invictus

CIA Top Secret File: the Us war in Syria planned since 1983 Un document nesigilat al Inteligenței SUA semnat de fostul funcționar al Agenției Centrale Graham Fuller, confirmă sângerosul proiect cu Israel și Turcia asupra opoziției lui Assad la conducta de petrol a Fratiei Musulmane. de Fabio Giuseppe Carlo Carisio pentru VT Italia Siria este […]

via Arhiva secretă de top a CIA: războiul SUA din Siria planificat din 1983 — Invictus

Giant Radio Telescope in China Just Detected Repeating Signals From Across Space

Vă amintiți, presupun, de acel spectaculos telescop de dimensiuni gigantice ascuns într-o vale înconjurată de munți în China, din urmă cu câțiva ani? Ei bine, Five-hundred-meter Aperture Spherical Radio Telescope (FAST) a recepționat un semnal spațial misterios cunoscut sub numele de explozie radio rapidă.

Exploziile radio rapide sau FRB sunt impulsuri de energie scurte, dar puternice, sosite din cele mai îndepărtate adâncimi ale cosmosului. Primul a fost reperat în 2007 și, de atunci, am descoperit din ce în ce mai multe.

Deși astronomii au făcut recent progrese interesante în urmărirea FRB-urilor, pur și simplu nu știm exact ce sunt aceste semnale sau cum au fost produse. Poate că sunt cauzate de găuri negre sau stele de neutroni, numite magnetars.

Ceea ce este interesant în ceea ce privește detectarea de FAST este faptul că această explozie rapidă de unde radio este un semnal repetitiv. Explozia este cunoscută oficial sub denumirea de FRB 121102: înregistrată pentru prima dată în 2012 la Observatorul Arecibo din Puerto Rico, și a apărut de atunci de mai multe ori .

Cercetătorii remarcă faptul că semnalul a parcurs aproximativ 3 miliarde de ani-lumină prin Univers pentru a ajunge până la noi.

FAST s-a fixat pe FRB 121102 pe 30 august, înainte de a înregistra zeci de impulsuri ulterioare (în ziua de 3 septembrie, au fost detectate peste 20 de impulsuri). Deci, acesta pare a fi un FRB deosebit de persistent.

The 19-beam receiver de pe FAST este deosebit de sensibil la semnalele radio, acoperind intervalul de frecvență de 1.05-1.45 GHz, ceea ce îl face perfect pentru a-l urmări pe FRB 121102.

Cu cât putem face mai multe observații cu privire la aceste FRB, cu atât cresc șansele noastre de a reuși să rezolvăm dilema a ceea ce sunt. O idee ar fi că FRB sunt produse de dezintegrarea crustelor anumitor tipuri de stele neutronice.

O altă ipoteză susține că diferite FRB au de fapt cauze diferite, ceea ce poate explica de ce se repetă FRB 121102, iar altele nu par să facă acest lucru. Măcar acum putem să identificăm de unde provin aceste explozii misterioase de radiații electromagnetice.

Putem adăuga datele culese de FAST la baza noastră de date în creștere cu cunoștințe despre aceste fenomene spațiale atât de intrigante. Echipa de astronomi a reușit deja să elimine interferențele produse de aeronave și sateliți din măsurătorile lor.

„Cred că este atât de uimitor că natura produce ceva de genul acesta”, a spus fizicianul Ziggy Pleunis de la Universitatea McGill, pentru ScienceAlert, după ce a ajutat la detalierea a opt noi FRB-uri într-o lucrare publicată luna trecută.

„De asemenea, cred că există o informație foarte importantă în acea structură, pe care trebuie doar să vedem cum să o decodificăm și este foarte distractiv să încercăm să ne dăm seama exact care este aceasta.”

***

Îngropat în palide toamne

Stau în saună și asud.

Mai ridic o treaptă și simt că nu mai am aer.

Cobor și ea parcă mă citește:

− Ce-i?

− Nimic important, ceasul ticăie mai repede, acolo sus.

− Cine te pune?

− Da. Asta-i! Cine mă pune. Anul trecut mi-aduceai păhărelul de votcă acolo. Am început să cobor treptele, o scară cu o unică destinație.

− Bea votca aia, ai astenie de toamnă.

− Probabil.

Dau păhăruțul pe gât și-l simt cum se rostogolește la vale arzând totul în drumul lui. Deschid gura și sorb scoica de manciuria cu un vârf de icre aurii. Animalul îmi mulțumește și mă răsucesc spre ea:

− Vino! Vezi? Înainte doar să mă fi atins, doar să te fi privit, panteră neagră, și toți neuronii îmi explodau. Acum, mă atingi și tot ce simt e doar o frecare a două bucăți de piele.

− Răbdare!

Se prelinge pe mine și simt o zvâcnire, o amintire de senzații. Natura își face datoria, încă, dar eu rămân nemulțumit și flasc.

Ea mă simte și se retrage, încet, discret.

Mai cobor o treaptă, două, trei…

Aici e frig.

Frigul îmi îngheață stropii de transpirație pe pieptul cu țâțe parcă de femeie, îmi strânge dureros sexul, mă cocoșează:

„Ce-ai fost și ce-ai ajuns, Mihail Mihailovici! Dar lasă că moartea va veni, iar apoi o vei lua-o de la capăt și vei fi pe cât ai fost ba chiar mai mult decât atât!”

***

Imaginea zilei – Cat on steps

Ad AstraCredit: 20th Century Fox/Disney SCIENCE BEHIND THE FICTION: WHAT IF, LIKE AD ASTRA SUGGESTS, THERE ARE NO ALIENS?

On the surface, Ad Astra appears to be a sojourn into familiar science fiction territory. A look at the trailer promises space-faring technology which, while advanced, feels not far off. There are vast structures, explosions, and the promise of a journey to the edge of the solar system, but not before we get a road warrior rover battle on the Moon, the likes of which would make George Miller shiver.

The film, directed by James Gray and starring Brad Pitt, is dressed in all the things that make science fiction exciting, but underneath is something much more intimate and a whole lot more true. Something… lonely.

**Spoilers for Ad Astra below**

Roy McBride (Pitt) has always wanted to be an astronaut. Lucky for him, it isn’t such an elite calling in his time (a nebulous near future). Humanity has expanded beyond Earth, setting up colonies on the Moon and Mars. And it helps that his father is a famous hero of the stars, leader of the first mission to the edge of the solar system. Roy’s father led a team of explorers to Neptune-orbit, beyond the interference of the inner solar system, in search of extraterrestrial life. The mission lost contact in the deeps of space and the crew is presumed dead.

In the end, the great irony of Ad Astra is that, while humanity has advanced and expanded its reach, Roy is utterly alone. It’s a point hammered home at the end of the film, when Roy finally finds his still-alive father and learns that, even after all these years, all they’ve discovered is that humanity remains alone in the universe.

Ad Astra certainly delivers action and some incredible visuals, it exists almost entirely on a stage of quiet contemplation and, when the thinking is done, you’re left with an answer you might not have wanted. Humans are alone in the universe, meaning we’ll have to live with each other, and perhaps more urgently, ourselves.

So, is Ad Astra‘s revelation that there are no aliens out there true, and if so, why is that fact so quietly devastating?

WHERE IS EVERYBODY?

One cannot embark upon this question without first discussing Enrico Fermi. In 1950, during lunch with some colleagues, Fermi, a physicist, made two seemingly obvious observations. First that the universe is very old, and second, that it is very large. He questioned, therefore, that given the age and size of the universe, it should have had ample time to fill itself with all manner of intelligent life. After all, we’re here, and there’s no particular reason to suspect we’re unique. So, where exactly is everyone?

This became known as the Fermi Paradox, the two seemingly incompatible truths that the celestial neighborhood ought to be heavily trafficked while we appear to be alone on a deserted island.

It seems a foregone conclusion, especially when considering the rapid rate of technological advancement we’re experiencing. In only a few decades we went from first flight, to walking on the Moon.

While it’s difficult to imagine the technology of the next century or the ones that follow, it doesn’t seem unrealistic (assuming we’re still around) that we’d settle our own solar system and continue onward. What might we accomplish in a thousand years, or a million? The universe has existed for several billion years. Shouldn’t we expect advanced civilizations with a considerable head start? Mightn’t they already have explored and settled the stars, scattering their footprints and the evidence of their presence?

Yet, when we look to the stars, we find a stunningly beautiful, yet entirely empty arena.

CAN WE SOLVE THE DRAKE EQUATION?

Dr. Frank Drake made the question of „where is everybody” a little more concrete — and more complicated — while working at the National Radio Astronomy Observatory in Green Bank, West Virginia. Drake suggested an equation which, if all the variables were known, could calculate the number of advanced civilizations in our galaxy.

The actual equation is little more than a string of variables, including the average rate of star formation per year in our galaxy, the fraction of those stars with planets, the fraction of those planets which are habitable, the fraction of those that succeed in developing life, the fraction of those that develop intelligent life, the fraction of those that develop interstellar communication, and the average length of time such civilizations could survive.

If we knew each of the variables for this proposed equation, we could solve for (N), the number of existing intelligent life forms we could contact in the universe. The trouble is, we have almost no empirical data to go on. We’ve got a pretty good idea as to the first bit, the rate of star formation in the galaxy, and as we continue to discover exo-planets, our view to the next couple bits improves. In fact, when it comes to planets in the habitable zone of their parent stars, evidence suggests they exist around approximately one-fifth of stars in the Milky Way.

The rest, however, is pure speculation.

When it comes to the frequency of life in the universe, let alone our own galaxy, we only have one data point. Us. The best we can say is that life can exist, whether it does anywhere else, remains to be seen. Ultimately, when using the Drake equation, the results tend to say a whole lot more about the biases of the people plugging in the numbers than it does about reality.

Still, there’s some inherent expectation in each of us that there must be other life in the universe. Paraphrasing Jodi Foster’s character in Contact, if we are alone in the universe, it seems like an awful waste of space. But science demands that we examine the evidence, and right now all we can say is it appears as though we’re on our own.

Scientists and thinkers have suggested an array of explanations for why that might be.

Maybe it’s that the Earth truly is unique, though that seems increasingly unlikely. It might be that we’re simply ahead of the curve. Life might be common but it hasn’t yet had the chance to gain a foothold.

WE WEREN’T ALWAYS ALONE, BUT WE ARE NOW

There are also more bleak explanations, namely that intelligent civilizations tend to destroy themselves, something of considerable speculation given our own violent and misguided tendencies. It might also be that the universe wipes out life. The Earth has already had five known extinction-level events and another could happen at any time. We’re one asteroid or gamma-ray burst from annihilation.

It might also be that we’re just not addressing the problem in the right way. Perhaps life is common, but we’re looking in the wrong places or for the wrong things. Maybe other intelligences are so advanced we can’t recognize them when we encounter them. Or maybe we’re being intentionally avoided.

There are any number of reasons to explain our lack of contact in an environment full of cosmic neighbors. The lack of evidence might not actually be evidence that we’re literally alone.

It might be that we’re just not smart enough, interesting enough, or important enough to be invited to the party.

Of course, it might be a matter of distance. We’ve only been looking in a concerted way for a handful of decades. The universe is large, insanely, astronomically vast, and it takes a while for our messages or the messages of anyone else to travel the distance. Though, that’s another problem Ad Astra seems to have solved.

UNIVERSAL LONG-DISTANCE CHARGES

If human history has proven anything, it’s that we’re pretty good at looking at our natural limitations and casting them aside. We see vast oceans, seemingly impenetrable barriers, and we build ships to cross them. We looked at the sky and saw not a limit, but another realm to make our own. We looked beyond the boundaries of our world and determined to send our machines and ourselves beyond it.

We’re not very good with respecting limitation, but there is one limit which defies even our ingenuity and spirit: light speed. It’s the universal constant, the boundary around which everything else is built. To break it would be to undo our very understanding of the nature of our reality.

When we send our machines into the cosmos, when we communicate with them and with one another, we have to account for the limitations of the speed of light.

For instance, if one day we do create a colony on Mars, it will mean we’ve overcome some of the greatest technological hurdles we’ve ever encountered in order to conquer another world. But you still won’t be able to place a phone call and have an ordinary conversation. The average distance to Mars is 225 million kilometers (140 million miles). Though that’s always in flux. Because of Earth and Mars’ respective orbits, the distance is always changing. At the closest distance, the two planets are 54.6 million kilometers (33.9 million miles).

Taking the average, Mars lies 12.5 light-minutes away. Meaning that a phone conversation would have a 25-minute delay between statements.

Any dreams we might have had for interplanetary cooperative video game sessions are out of the question. Even a game of chess could take days to complete.

Which makes it all the more curious that Brad Pitt’s character was able to send a message from Mars to Neptune and receive a response in a few moments. The distances involved there are even more staggering. The average distance from Mars to Neptune is 4,273,060,000 kilometers (2,655,279,484 miles) for a light-distance of nearly four hours. That means once a message was sent, you couldn’t expect a response for roughly eight hours, and that’s if the recipient replied right away. Interplanetary communication would be a whole lot of hurry up and wait.

But in Ad Astra, it appears as though McBride’s companions receive a reply almost immediately, suggesting they’d developed some form of communication capable of skirting light speed. Which means they’d be able to peer even farther into the cosmos in their search for life outside our solar system.

So, why, given this level of technology were Roy and all the rest of humanity still alone in the universe? It’s anyone’s guess, and it very well might be something we have to make peace with someday.

For reasons we may never know, we might ultimately conclude that we are all there is, at least within the sphere of existence we’re capable of observing. Perhaps it’s a reminder of Sagan’s famous words in his Pale Blue Dot speech: „Our planet is a lonely speck in the great enveloping cosmic dark. In our obscurity, in all this vastness, there is no hint that help will come to save us from ourselves… it underscores our responsibility to deal more kindly with one another, and to preserve and cherish the pale blue dot, the only home we’ve ever known.”

Credit: Universe today

Standard Model’s Greatest Puzzle. No other particles behave the way the elusive neutrino does, and that might unlock our greatest mysteries.

The Sudbury neutrino observatory, which was instrumental in demonstrating neutrino oscillations and the massiveness of neutrinos. With additional results from atmospheric, solar, and terrestrial observatories and experiments, we may not be able to explain the full suite of what we’ve observed with only 3 Standard Model neutrinos, and a sterile neutrino could still be very interesting as a cold dark matter candidate. (A. B. MCDONALD (QUEEN’S UNIVERSITY) ET AL., THE SUDBURY NEUTRINO OBSERVATORY INSTITUTE)

Every form of matter that we know of in the Universe is made up of the same few fundamental particles: the quarks, leptons and bosons of the Standard Model. Quarks and leptons bind together to form protons and neutrons, heavy elements, atoms, molecules, and all the visible matter we know of. The bosons are responsible for the forces between all particles, and — with the exception of a few puzzles like dark matter, dark energy, and why our Universe is filled with matter and not antimatter — the rules governing these particles explains everything we’ve ever observed.

Except, that is, for the neutrino. This one particle behaves so bizarrely and uniquely, distinct from all the others, that it’s the only Standard Model particle whose properties cannot be accounted for by the Standard Model alone. Here’s why.

Imagine you have a particle. It’s going to have a few specific properties that are intrinsically, unambiguously known. These properties include:

- mass,

- electric charge,

- weak hypercharge,

- spin (inherent angular momentum),

- color charge,

- baryon number,

- lepton number,

- and lepton family number,

as well as others. For a charged lepton, like an electron, values like mass and electric charge are known to an extraordinary precision, and those values are identical for every electron in the Universe.

Electrons, like all quarks and leptons, also have values for all of these other properties (or quantum numbers). Some of those values may be zero (such as color charge or baryon number), but the non-zero ones tell us something additional about each particle in question. Spin, for example, can be either +½ or -½ for the electron, which tells you something important: there’s a degree of freedom here.

It’s the reason why, if you bind an electron to a proton (or any atomic nucleus), there’s a 50/50 shot that the electron will have its spin aligned with the proton’s spin, and a 50/50 shot that they’ll be anti-aligned. An electron’s spin, relative to any axis you choose (x, y, and z, the electron’s direction of motion, the proton’s spin axis, etc.) is completely random.

Neutrinos, like electrons, are also leptons. Although they don’t have electric charge, they do have quantum numbers all their own. Just as an electron has an antimatter counterpart (the positron), the neutrino has an antimatter counterpart as well: the antineutrino. Although they were first theorized in 1930 by Wolfgang Pauli, the first neutrino detection didn’t take place until the mid-1950s, and actually involved antineutrinos produced by nuclear reactors.

Based on the properties of the particles produced by a neutrino interaction, we can reconstruct various properties of the neutrinos and antineutrinos that we see. One of them, in particular, stands out as incongruent with every other fermion in the Standard Model: spin.

Remember how there was a 50/50 shot that an electrons would have a spin of either +½ or -½? Well, that’s true for every quark and lepton in the Standard Model, except the neutrino.

- All six of the quarks and all six of the antiquarks can have spins that are either +½ or -½, with no exceptions.

- The electron, muon, and tau, as well as their antiparticles, are allowed spins of either +½ or -½, with no exceptions.

- But when it comes to the three types of neutrinos and the three types of antineutrinos, their spins are restricted.

There’s a good reason for this. Imagine you produce a matter/antimatter pair of particles. We’ll imagine three cases: one where the pair is of electrons and positrons, a second where the pair is of two photons (bosons that are their own antiparticle), and a third where the pair is a neutrino and an antineutrino. Starting at the creation point, where the particles first come into existence from some form of energy (via Einstein’s famous E = mc2), you can imagine what will happen for each of these cases.

1.) If you produce electrons and positrons, they’ll move away from one another in opposite directions, and both the electron and positron will have the options of spin being either +½ or -½ along any axis. So long as the total amount of angular momentum is conserved for the system, there are no restrictions on the directions in which electrons or positrons spin.

2.) If you produce two photons, they’ll also move away from one another in opposite directions, but their spins are highly constrained. Whereas an electron or positron could spin in any direction at all, a photon’s spin can only be oriented along the axis that this quantum of radiation propagates. You can imagine pointing your thumb in the direction the photon moves, but the spin is restricted by the direction your fingers curl around relative to your thumb: it can go clockwise (right-handed) or counterclockwise (left-handed) around the axis of rotation (+1 or -1; bosons have integer, rather than half-integer, spins), but no other spins are allowed.

3.) Now, we come to the neutrino and antineutrino pair, and it’s going to get weird. All of the neutrinos and antineutrinos we’ve ever detected are extraordinarily high in energy, meaning that they move at speeds so high that their motion is experimentally indistinguishable from the speed of light. Instead of behaving like electrons and positrons, we find that all neutrinos are left-handed (spin = +½) and all antineutrinos are right-handed (spin = -½).

Throughout most of the 20th century, it was taken as an unusual but quirky property of neutrinos: one that was allowed because they were thought to be completely massless. But a series of experiments and observatories involving neutrinos produced by the Sun and neutrinos produced by cosmic ray collisions with Earth’s atmosphere revealed a bizarre property of these elusive particles.

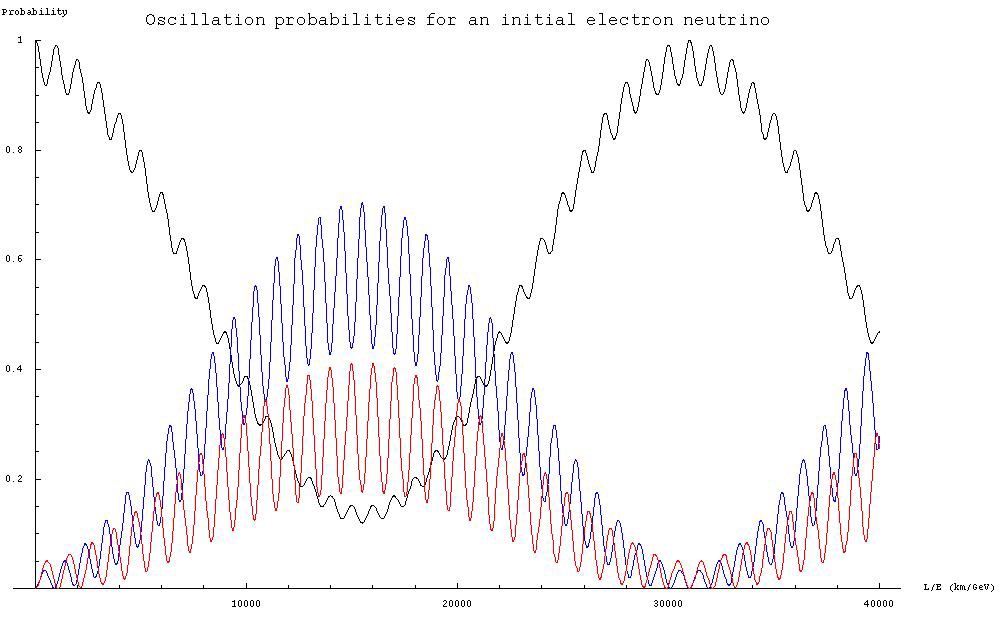

Instead of remaining the same flavor of neutrino or antineutrino (electron, muon, and tau; one corresponding to each of the three families of lepton), there is a finite probability that one type of neutrino can oscillate into another. The probability of this occurring depends on a number of factors that are still being explored, but one thing is certain: this behavior is only possible if neutrinos have a mass. It may be small, but it must be non-zero.

Although we don’t know which neutrino types have which mass, there are meaningful constraints that teach us profound truths about the Universe. From the neutrino oscillation data, we can determine that at least one of these three neutrinos has a mass that can be no less than a few hundredths of an electron-volt; that’s a lower limit.

On the other hand, brand new results from the KATRIN experiment constrain the electron neutrino’s mass to be less than 1.0 eV (directly), while astrophysical data from the cosmic microwave background and baryon acoustic oscillations constrain the sum of the masses of all three types of neutrino to be less than about 0.17 eV. Somewhere between these upper limits and the oscillation-informed lower limit lies the actual masses of the neutrinos.

But this is where the big puzzle comes in: if neutrinos and antineutrinos have mass, then it should be possible to turn a left-handed neutrino into a right-handed particle simply by either slowing the neutrino down or speeding yourself up. If you curl your fingers around your left thumb and point your thumb towards you, your fingers curl clockwise around your thumb. If you point your left thumb away from you, though, your fingers appear to curl counterclockwise instead.

In other words, we can change the perceived spin of a neutrino or antineutrino simply by changing our motion relative to it. Since all neutrinos are left-handed and all antineutrinos are right-handed, does this mean that you can transform a left-handed neutrino into a right-handed antineutrino simply by changing your perspective? Or does this mean that left-handed antineutrinos and right-handed neutrinos exist, but are beyond our current detection capabilities?

Believe it or not, unlocking the answer to this question could open the door to understanding why our Universe is made of matter and not antimatter. One of the four fundamental requirements for producing a matter-antimatter asymmetry from an initially symmetric state is for the Universe to behave differently if you replace all the particles with antiparticles, and a Universe where all your neutrinos are left-handed and all your antineutrinos are right-handed could give you exactly that.

The result of boosting yourself to view a left-handed neutrino from the opposite direction will shed a tremendous hint: if you see a right-handed neutrino, then they exist in this Universe, neutrinos are Dirac fermions, and there’s something more to learn. If you see a right-handed antineutrino, however, then neutrinos are Majorana fermions, and might point towards a solution (leptogenesis) to the matter-antimatter problem.

Our Universe, as we understand it today, is full of puzzles that we cannot explain. The neutrino is perhaps the only Standard Model particle whose properties have yet to be thoroughly uncovered, but there’s a tremendous hope here. You see, during the earliest stages of the Big Bang, neutrinos and antineutrinos are produced in tremendous numbers. Even today, only photons are more abundant. On average, there are around 300 neutrinos and antineutrinos per cubic centimeter in our Universe.

But the ones that were made in the Universe’s hot, early stages are special: as a result of being around for so long in our expanding Universe, they now move so slowly that they’re guaranteed to have fallen into a large halo encompassing every massive galaxy, including our own. These neutrinos and antineutrinos are everywhere, with minute but finite cross-sections, just waiting to be explored. When our experimental sensitivity catches up to the physical reality of relic neutrinos, we’ll be one step closer to understanding just how, exactly, our Universe came to be. Until then, neutrinos will likely remain the Standard Model’s greatest puzzle.

Foto-Observatorul de neutrini din Sudbury, care a contribuit la demonstrarea faptului cî neutrinii au masă și perioadă de oscilație. Având rezultate suplimentare din observatoarele și experimentele atmosferice, solare și terestre, s-ar putea să nu putem explica suita completă a ceea ce am observat cu doar 3 neutrini din modelul standard (A. B. MCDONALD (UNIVERSITATEA REGATULUI) ET AL. INSTITUTUL OBSERVATORIU SUDBURY NEUTRINO)

Fiecare formă de materie pe care o cunoaștem în Univers este formată din aceleași puține particule fundamentale: quark-urile, leptonii și bosonii modelului standard. Quark-urile și leptonii se leagă pentru a forma protoni și neutroni, elemente grele, atomi, molecule și toată materia vizibilă pe care o cunoaștem. Bosonii sunt responsabili pentru forțele dintre toate particulele și – cu excepția câtorva puzzle-uri precum materia întunecată, energia întunecată și de ce Universul nostru este plin de materie și nu de antimaterie – regulile care guvernează aceste particule sunt universale.

Cu excepția, adică… neutrino. Această particulă se comportă atât de bizar și unic, distinct de toate celelalte, încât este singura particulă ale cărei proprietăți nu pot fi contabilizate doar de modelul standard. Iată de ce.

Foto-Particulele și antiparticulele modelului standard respectă tot felul de legi de conservare, dar există ușoare diferențe între comportamentul anumitor perechi de particule / antiparticule care da indicii ale originii baryogenezei. (E. SIEGEL / DUPĂ GALAXIE)

Imaginează-ți că ai o particulă. Va avea câteva proprietăți specifice care sunt cunoscute intrinsec, fără echivoc. Aceste proprietăți includ:

- mass,

- electric charge,

- weak hypercharge,

- spin (inherent angular momentum),

- color charge,

- baryon number,

- lepton number,

- and lepton family number,

precum și altele. Pentru o leptonă încărcată, ca un electron, valorile precum masa și sarcina electrică sunt cunoscute cu o precizie extraordinară, iar aceste valori sunt identice pentru fiecare electron din Univers.

Electronii, ca și toate quark-urile și leptonii, au și valori pentru toate aceste alte proprietăți (sau numere cuantice). Unele dintre aceste valori pot fi zero (cum ar fi încărcarea culorii sau numărul barionului), dar cele care nu sunt zero ne spun ceva suplimentar despre fiecare particulă în cauză. Spinul, de exemplu, poate fi + + ½ sau -½ pentru electron, ceea ce vă spune ceva important: există un grad de libertate aici.

Foto-Linia de hidrogen de 21 de centimetri se produce atunci când un atom de hidrogen care conține o combinație de protoni / electroni cu rotiri aliniate (de sus) se întoarce pentru a avea rotiri anti-aliniate (de jos), emitând un foton particular cu o lungime de undă foarte caracteristică. Configurația cu spin opus în nivelul de energie n = 1 reprezintă starea de bază a hidrogenului, dar energia punctului său zero este o valoare finită, non-zero. Această tranziție face parte din structura hiperfină a materiei, depășind chiar și dincolo de structura fină pe care o experimentăm mai des. Pentru electroni și protoni liberi, există o șansă de 50/50 ca aceștia să se lege fie în stările aliniate, fie în cele anti-aliniate. (TILTEC DE COMUNE WIKIMEDIA)

Este motivul pentru care, dacă legați un electron la un proton (sau la orice nucleu atomic), există o șansă de 50/50, care va avea spinul aliniat la spinul protonului sau nu. Spinul unui electron, în raport cu orice axă pe care o alegeți (x, y și z, direcția de mișcare a electronului, axa de rotire a protonului etc.) este complet aleatorie.

Neutrinii, ca și electronii, sunt și leptoni. Deși nu au încărcări electrice, ei au toate numerele cuantice. La fel cum un electron are un omolog antimaterie (pozitronul), neutrino are și un omolog antimaterie: antineutrino. Deși a fost teoretizat pentru prima dată în 1930 de Wolfgang Pauli, prima detectare a neutrinilor nu a avut loc până la jumătatea anilor ’50 și a implicat de fapt antineutrino produși de reactoarele nucleare.

Foto- Neutrino a fost propus pentru prima dată în 1930, dar nu a fost detectat până în 1956, în reactoarele nucleare. În anii și deceniile care au trecut de atunci, am detectat neutrini în Soare, în razele cosmice și chiar în supernove. Aici, vedem construcția rezervorului folosit în experimentul cu neutrino solar în mina de aur Homestake din anii ’60. (LABORATOR NAȚIONAL BROOKHAVEN)

Pe baza proprietăților particulelor produse de o interacțiune neutrino, putem reconstrui diverse proprietăți ale neutrinilor și antineutrinilor. Una dintre ele, în special, se remarcă ca fiind incongruentă cu fiecare alt fermion din Modelul Standard: rotire.

Vă amintiți cum a existat o șansă de 50/50 că un electron va avea un rotire de + ½ sau -½? Ei bine, acest lucru este valabil pentru fiecare quark și lepton din modelul standard, cu excepția neutrinului.

Toate cele șase quark-uri și toate cele șase antiquarks pot avea rotiri care sunt + ½ sau -½, fără excepții.

Electronul, muonul și tau-ul, precum și antiparticulele lor, sunt permise rotiri de + ½ sau -½, fără excepții.

Dar când vine vorba de cele trei tipuri de neutrino și cele trei tipuri de antineutrino, rotirile lor sunt restricționate.

Foto- Producția de perechi de materie / antimaterie (stânga) din energie pură este o reacție complet reversibilă (dreapta), cu materie / antimaterie anihilându-se înapoi în energie pură. Când un foton este creat și apoi distrus, acesta experimentează acele evenimente simultan, fiind în același timp incapabil să experimenteze orice altceva. Dacă acționați în cadrul de repaus din centrul momentului (sau din centrul de masă), perechile de particule / antiparticule (inclusiv doi fotoni) se vor închide la unghi de 180 de grade unul cu celălalt. (DMITRI POGOSYAN / UNIVERSITATEA ALBERTA)

Există un motiv întemeiat pentru acest lucru. Imaginați-vă că produceți o pereche de particule antimaterie. Ne vom imagina trei cazuri: unul în care perechea este de electroni și pozitroni, un al doilea în care perechea este din doi fotoni (bosoni care sunt propriile lor antiparticule) și un al treilea în care perechea este un neutrino și un antineutrino. Începând din punctul de creație, în care particulele apar prima dată dintr-o formă de energie (prin celebrul E = mc2) al lui Einstein, vă puteți imagina ce se va întâmpla pentru fiecare dintre aceste cazuri?

1.) Dacă produci electroni și pozitroni, aceștia se vor îndepărta unul de celălalt în direcții opuse și atât electronul cât și pozitronul vor avea opțiunile de a fi fie + ½ sau -½ de-a lungul oricărei axe. Atât timp cât se păstrează cantitatea totală de moment unghiular pentru sistem, nu există restricții cu privire la direcțiile în care se învârtesc electronii sau pozitronii.

Foto- O polarizare circulară din stânga este inerentă la 50% din fotoni și o polarizare circulară din dreapta este inerentă celorlalte 50%. Ori de câte ori sunt creați doi fotoni, rotirile lor (sau momentele unghiulare intrinseci, dacă doriți) se rezumă întotdeauna astfel încât momentul unghiular total al sistemului să fie conservat. Nu există impulsuri sau manipulări pe care le putem efectua pentru a modifica polarizarea unui foton. (COMUNE E-KARIMI / WIKIMEDIA)

2.) Dacă produceți doi fotoni, se vor îndepărta și unul de celălalt în direcții opuse, dar rotirile lor sunt foarte restrânse. În timp ce un electron sau un pozitron s-ar putea roti în orice direcție, spinul unui foton poate fi orientat numai de-a lungul axei pe care o propagă această cantitate de radiații. Vă puteți imagina îndreptându-vă degetul mare în direcția în care se mișcă fotonul, dar rotirea este restricționată de direcția în care degetele se încolăcesc în raport cu degetul mare: poate merge în sensul acelor de ceasornic (dreapta) sau în sensul acelor de ceasornic (stânga) în jurul axei rotire (+1 sau -1; bosonii au numere întregi, mai degrabă decât jumătate întregi, rotiri), dar nu sunt permise alte rotiri.

3.) Acum, ajungem la perechea neutrino și antineutrino și va deveni ciudat. Toți neutrinii și antineutrinii pe care i-am detectat vreodată au o energie extraordinar de mare, ceea ce înseamnă că se mișcă la viteze atât de mari încât mișcarea lor este indistinguibilă experimental de viteza luminii. În loc să ne comportăm ca electroni și pozitroni, descoperim că toți neutrinii sunt stângaci (spin = + ½) și că toți antineutrinii sunt dreptaci (spin = -½).

Foto- Dacă prindeți un neutrino sau un antineutrino care se deplasează într-o direcție anume, veți constata că momentul său unghiular intrinsec prezintă o rotire în sensul acelor de ceasornic sau în sens invers acelor de ceasornic, corespunzător faptului că particula în cauză este neutrino sau antineutrino. Dacă neutrinii dreaptaci (și antineutrinii stângaci) sunt reali sau nu este o întrebare fără răspuns, care ar putea debloca multe mistere despre cosmos. (HIPPERFIZICA / R NAVE / GEORGIA UNIVERSITATEA DE STAT)

În secolul XX, aceasta a fost luată ca o proprietate neobișnuită, dar ciudată, a neutrinilor: una care a fost permisă, deoarece se credea că sunt complet fără masă. Dar o serie de experimente și observatorii care implică neutrini produși de Soare și neutroni produși prin coliziunile de raze cosmice cu atmosfera Pământului au relevat o proprietate bizară a acestor particule evazive.

În loc să rămână aceeași formă de neutrino sau antineutrino (electron, muon și tau; una corespunzătoare fiecăreia dintre cele trei familii de lepton), există o probabilitate finită ca un tip de neutrino să oscileze. Probabilitatea ca aceasta să apară depinde de o serie de factori care sunt încă studiați, dar un lucru este sigur: acest comportament este posibil numai dacă neutrinii au o masă. Poate fi mic, dar diferit de zero.

Foto- Dacă începeți cu un neutrin de electron (negru) și îi permiteți să călătorească fie prin spațiu gol, fie prin materie, acesta va avea o anumită probabilitate de a oscila, lucru care se poate întâmpla doar dacă neutrinii au mase foarte mici, dar care nu sunt zero. Rezultatele experimentului neutrinilor solari și atmosferici sunt în concordanță unele cu altele, dar nu cu suita completă de date despre neutrino. (STRAIT DE UTILIZATOR COMUN WIKIMEDIA)

Deși nu știm ce tipuri de neutrino au masă, există constrângeri semnificative care ne învață adevăruri profunde despre Univers. Din datele de oscilație ale neutrinilor, putem determina că cel puțin unul dintre acești trei neutrini are o masă care poate fi nu mai puțin de câteva sutimi de electroni-volt; aceasta este o limită inferioară.

Pe de altă parte, rezultatele noi din experimentul KATRIN constrâng masa neutrinului de electroni să fie mai mică de 1,0 eV (direct), în timp ce datele astrofizice din fundalul microundelor cosmice și oscilațiile acustice ale baronului constrâng suma maselor celor trei tipuri de neutrino să fie mai mic de aproximativ 0,17 eV. Undeva între aceste limite superioare și limita inferioară se află masele reale ale neutrinilor.

O scară logaritmică care arată masele fermionilor modelului standard: quark-urile și leptonele. Rețineți minusculele maselor de neutrino. Cu cele mai noi rezultate KATRIN, neutrinul de electroni este mai mic de 1 eV în masă, în timp ce din datele din Universul timpuriu, suma celor trei mase de neutrini nu poate fi mai mare de 0,17 eV. Acestea sunt cele mai bune limite superioare pentru masa neutrino. (HITOSHI MURAYAMA)

Dar aici vine marele puzzle: dacă neutrinii și antineutrinii au masă, atunci ar trebui să fie posibil să transformăm un neutrin din stânga într-o particulă dreaptă pur și simplu încetinind neutrino-ul sau grăbindu-vă. Dacă îți rotești degetele în jurul degetului mare stâng și îți îndreptați degetul mare spre tine, degetele se curbă în sens orar în jurul degetului mare. Dacă îți îndrepți degetul stâng departe de tine, în schimb, degetele par să se curbe în sens invers acelor de ceasornic.

Cu alte cuvinte, putem schimba spinul perceput al unui neutrino sau antineutrino pur și simplu schimbând mișcarea noastră în raport cu acesta. Deoarece toți neutrinii sunt stângaci și toți antineutrinii sunt dreptaci, asta înseamnă că puteți transforma un neutrin din stânga într-un antineutrino drept doar schimbând perspectiva? Sau înseamnă asta că există antineutrini stângaci și neutrini stângaci, dar sunt dincolo de capacitățile noastre actuale de detectare?

Foto- Experimentul GERDA, din urmă cu un deceniu, s-a ocupat de dubla descompunere beta a neutrinilor . Experimentul MAJORANA, prezentat aici, are potențialul de a detecta în sfârșit această rară descompunere. (EXPERIMENTUL / UNIVERSITATEA DE WASHINGTON MAJORANA NEUTRINOLESS DOUBLE-BETA DECAY)

Credeți sau nu, răspunsul la această întrebare ar putea deschide ușa înțelegerii de ce Universul nostru este format din materie și nu antimaterie. Una dintre cele patru cerințe fundamentale pentru producerea unei asimetrii antimaterie materie dintr-o stare inițial simetrică este ca Universul să se comporte diferit dacă înlocuiți toate particulele cu antiparticule și un Univers în care toți neutrinii dvs. sunt stângaci și toți antineutrinii dvs. sunt mâna dreaptă ar putea să vă dea exact asta.

Rezultatul creșterii dvs. pentru a vedea un neutrino din stânga din direcția opusă va arunca un indiciu extraordinar: dacă vedeți un neutrino cu mâna dreaptă, atunci există în acest Univers, neutrinii sunt fermionii Dirac și mai există ceva de învățat. Dacă vedeți totuși un antineutrino drept, atunci neutrinii sunt fermioni Majorana și ar putea îndrepta spre o soluție (leptogeneză) la problema materiei-antimaterie.

Încă nu am măsurat masele absolute de neutrini, dar putem spune diferențele dintre masele de măsurători solare și neutrino atmosferice. O scară de masă de aproximativ ~ 0,01 eV pare să se potrivească cel mai bine datelor și patru parametri totale (pentru matricea de amestecare) sunt necesari pentru a înțelege proprietățile neutrino. Rezultatele LSND și MiniBooNe, însă, sunt incompatibile cu această imagine simplă și ar trebui fie confirmate, fie contrazise în următoarele luni. (HAMISH ROBERTSON, LA SIMPOSIUL CAROLINA 2008)

Universul nostru, așa cum îl înțelegem astăzi, este plin de puzzle-uri pe care nu le putem explica. Neutrino este probabil singura particulă cu model standard ale cărei proprietăți nu au fost încă descoperite în detaliu, dar există o speranță imensă aici. Vedeți, în primele etape ale Big Bang-ului, neutrinos și antineutrinos au fost produși într-un număr extraordinar. Chiar și astăzi, doar fotonii sunt mai abundenți. În medie, în Universul nostru există în jur de 300 de neutrini și antineutrini pe centimetru cub.

Dar ccondițiile din etapele timpurii fierbinți ale Universului au fost speciale: ca urmare a faptului că stau atât de mult timp în Universul nostru în expansiune, acum se mișcă extrem de încet în galaxii, inclusiv a noastră. Acești neutrini și antineutrini sunt peste tot și abia așteaptă să fie descoperiți. Când sensibilitatea noastră experimentală se va apropia de realitatea fizică a neutrinilor religve, vom fi cu un pas mai aproape de a înțelege exact cum a ajuns universul nostru. Până atunci, probabil, neutrinii vor rămâne cel mai mare puzzle al modelului standard.

***

Imaginea zilei – Hotarul spre nemărginire

Just How Feasible is a Warp Drive?

It’s hard living in a relativistic Universe, where even the nearest stars are so far away and the speed of light is absolute. It is little wonder then why science fiction franchises routinely employ FTL (Faster-than-Light) as a plot device. Push a button, press a pedal, and that fancy drive system – whose workings no one can explain – will send us to another location in space-time.

However, in recent years, the scientific community has become understandably excited and skeptical about claims that a particular concept – the Alcubierre Warp Drive – might actually be feasible. This was the subject of a presentation made at this year’s American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics Propulsion and Energy Forum, which took place from August 19th to 22nd in Indianapolis.

This presentation was conducted by Joseph Agnew – an undergraduate engineer and research assistant from the University of Alabama in Huntsville’s Propulsion Research Center (PRC). As part of a session titled “The Future of Nuclear and Breakthrough Propulsion”, Agnew shared the results of a study he conducted titled “An Examination of Warp Theory and Technology to Determine the State of the Art and Feasibility“.

As Agnew explained to a packed house, the theory behind a warp propulsion system is relatively simple. Originally proposed by Mexican physicist Miguel Alcubierre in 1994, this concept for an FTL system is viewed by man as a highly theoretical (but possibly valid) solution to the Einstein field equations, which describe how space, time and energy in our Universe interact.

In layman’s terms, the Alcubierre Drive achieves FTL travel by stretching the fabric of space-time in a wave, causing the space ahead of it to contract while the space behind it expands. In theory, a spacecraft inside this wave would be able to ride this “warp bubble” and achieve velocities beyond the speed of light. This is what is known as the “Alcubierre Metric”.

Interpreted in the context of General Relativity, the interior of this warp bubble would constitute the inertial reference frame for anything inside it. By the same token, such bubbles can appear in a previously flat region of spacetime and exceed the speed of light. Since the ship is not moving through space-time (but moving space-time itself), conventional relativistic effects (like time dilation) would not apply.

In short, the Alcubierre Metric allows for FTL travel without violating the laws of relativity in the conventional sense. As Agnew told Universe Today via email, he was inspired by this concept as early as high school and has been pursuing it ever since:

“I delved into mathematics and science more, and, as a result, started to become interested in science fiction and advanced theories on a more technical scale. I started watching Star Trek, the Original series and The Next Generation, and noticed how they had predicted or inspired the invention of cell phones, tablets, and other amenities. I thought about some of the other technologies, such as photon torpedoes, phasers, and warp drive, and tried to research both what the ‘star trek science’ and ‘real world science equivalent’ had to say about it. I then stumbled across the original paper by Miguel Alcubierre, and after digesting it for a while, I started pursuing other keywords and papers and getting deeper into the theory.”

While the concept was generally dismissed for being entirely theoretical and highly speculative, it has had new life breathed into it in recent years. The credit for this goes largely to Dr. Harold “Sonny” White, the Advanced Propulsion Team Lead for at the NASA Johnson Space Center’s Advanced Propulsion Physics Laboratory (aka. “Eagleworks Laboratory”).

During the 100 Year Starship Symposium in 2011, Dr. White shared some updated calculations of the Alcubierre Metric, which were the subject of a presentation titled “Warp Field Mechanics 101” (and a study of the same name). According to Dr. White, Alcubierre’s theory was sound but needed some serious testing and development. Since then, he and his colleagues have been doing these very things through the Eagleworks Lab.

In a similar vein, Agnew has spent much of his academic career researching the theory and mechanics behind warp mechanics. Under the mentorship of Dr. Jason Cassibry – an associate professor of mechanical and aerospace engineering and a faculty member of the UAH’s Propulsion Research Center – Agnew’s work has culminated in a study that addresses the major hurdles and opportunities presented by warp mechanics research.

As Agnew related, one of the greatest is the fact that the concept of the “warp drive” is still not taken very seriously in scientific circles:

“In my experience, the mention of warp drive tends to bring chuckles to the conversation because it is so theoretical and right out of science fiction. In fact, often it is met with dismissive remarks, and used as an example of something totally outlandish, which is understandable. I know in my own case, I initially had grouped it, mentally, into the same category as typical superluminal concepts, since obviously they all violate the ‘speed of light is the ultimate speed’ assumption. It wasn’t until I dug into the theory more carefully that I realized it did not have these problems. I think there would/will be much more interest when individuals delve into the progress that has been made. The historically theoretical nature of the idea is also itself a likely deterrent, as it’s much more difficult to see substantial progress when you are looking at equations instead of quantitative results.“

While the field is still in its infancy, there have been a number of recent developments that have helped. For example, the discovery of naturally occurring gravitational waves (GWSs) by LIGO scientists in 2016, which both confirmed a prediction made by Einstein a century ago and proves that the basis for the warp drive exists in nature. As Agnew indicated, this is perhaps the most significant development, but not the only one:

“In the past 5-10 years or so, there has been a lot of excellent progress along the lines of predicting the anticipated effects of the drive, determining how one might bring it into existence, reinforcing fundamental assumptions and concepts, and, my personal favorite, ways to test the theory in a laboratory.

“The LIGO discovery a few years back was, in my opinion, a huge leap forward in science, since it proved, experimentally, that spacetime can ‘warp’ and bend in the presence of enormous gravitational fields, and this is propagated out across the universe in a way that we can measure. Before, there was an understanding that this was likely the case, thanks to Einstein, but we know for certain now.”

Since the system relies on the expansion and compression of spacetime, said Agnew, this discovery demonstrated that some of these effects occur naturally. “Now that we know the effect is real, the next question, in my mind, is, ‘how do we study it, and can we generate it ourselves in the lab?’” he added. “Obviously, something like that would be a huge investment of time and resources, but would be massively beneficial.”

Of course, the Warp Drive concept requires additional support and numerous advances before experimental research will be possible. These include advances in terms of the theoretical framework as well as technological advancements. If these are treated as “bite-size” problems instead of one massive challenge, said Agnew, then progress is sure to be made:

“In essence, what is needed for a warp drive is a way to expand and contract spacetime at will, and in a local manner, such as around a small object or ship. We know for certain that very high energy densities, in the form of EM fields or mass, for example, can cause curvature in spacetime. It takes enormous amounts to do so, however, with our current analysis of the problem.”

“On the flipside, the technical areas should try to refine the equipment and process as much as possible, making these high energy densities more plausible. I believe there is a chance that once the effect can be duplicated on a lab scale, it will lead to a much deeper understanding of how gravity works, and may open the door to some as-yet-undiscovered theories or loopholes. I suppose to summarize, the biggest hurdle is the energy, and with that comes technological hurdles, needing bigger EM fields, more sensitive equipment, etc.“

The sheer amount of positive and negative energy needed to create a warp bubble remains the biggest challenge associated with Alcubierre’s concept. Currently, scientists believe that the only way to maintain the negative energy density required to produce the bubble is through exotic matter. Scientists also estimate that the total energy requirement would be equivalent to the mass of Jupiter.

However, this represents a significant drop from earlier energy estimates, which claimed that it would take an energy mass equivalent to the entire Universe. Nevertheless, a Jupiter-mass amount of exotic matter is still prohibitively large. In this respect, significant progress still needs to be made to scale the energy requirements down to something more realistic.

The only foreseeable way to do this is through further advances in quantum physics, quantum mechanics and metamaterials, says Agnew. As for the technical side of things, further progress will need to be made in the creation of superconductors, interferometers, and magnetic generators. And of course, there’s the issue of funding, which is always a challenge when it comes to concepts that are deemed to be “out there”.

But as Agnew states, that’s not an insurmountable challenge. Considering the progress that has been made so far, there are reason to be positive about the future:

“The theory has borne out thus far that it is well worth pursuing, and it is easier now than before to provide evidence that it is legitimate. In terms of justifications for allocation of resources, it is not hard to see that the ability to explore beyond our Solar System, even beyond our galaxy, would be an enormous leap for mankind. And the growth in technology resulting from pushing the bounds of research would certainly be beneficial.”

Like avionics, nuclear research, space exploration, electric cars, and reusable rocket boosters, the Alcubierre Warp Drive seems destined to be one of those concepts that will have to fight its way uphill. But if these other historical cases are any indication, eventually it may pass a point of no return and suddenly seem entirely possible!

And given our growing preoccupation with exoplanets (another exploding field of astronomy), there is no shortage of people hoping to send missions to nearby stars to search for potentially habitable planets. And as the aforementioned examples certainly demonstrate, sometimes, all that’s needed to get the ball rolling is a good push…

Nu-i ușor să trăiești într-un Univers relativist, unde chiar și cele mai apropiate stele sunt atât de departe, iar viteza luminii atât de mică și absolută. Nu este de mirare atunci de ce francizele science fiction folosesc de regulă FTL (Faster-than-Light) ca dispozitiv de recuzită. Apăsați un buton, apăsați o petală, și acel sistem de acționare fantezist – a cărui funcționare nimeni nu o poate explica – ne va trimite într-o altă locație din spațiu-timp. Cu toate acestea, în ultimii ani, comunitatea științifică a devenit mai puțin sceptică în ceea ce privește afirmațiile că un anumit concept – Alcubierre Warp Drive – ar putea fi de fapt posibil. Acesta a fost subiectul unei prezentări făcute la Institutul American de Aeronautică și Forumul pentru Propulsie și Energie pentru Astronautică din acest an, care a avut loc în perioada 19 – 22 august la Indianapolis. Această prezentare a fost realizată de Joseph Agnew – un inginer universitar și asistent de cercetare de la Universitatea Alabama din Huntsville’s Propulsion Research Center (PRC). În cadrul unei sesiuni intitulată „Viitorul propulsiilor inovatoare și nucleare”, Agnew a împărtășit rezultatele unui studiu pe care l-a realizat intitulat „O examinare a teoriei și a tehnicii Warp pentru a determina viabilitatea ei în lumina tehnologiilor de ultimă oră”.

După cum a explicat Agnew în fața unei săli de conferințe plină ochi, teoria din spatele unui sistem de propulsie Warp este relativ simplă. Propus inițial de fizicianul mexican Miguel Alcubierre în 1994, conceptul pentru un sistem FTL este considerat ca o soluție extrem de teoretică (dar posibil valabilă) pentru ecuațiile de câmp ale lui Einstein, care descriu modul în care interacționează spațiul, timpul și energia din Universul nostru.

În termeni profani, Alcubierre Drive realizează deplasarea FTL prin obligarea țesăturii spațiu-timp să se vălurească, determinând spațiul din fața sa să se contracte în timp ce spațiul din spatele său se dilate. În teorie, o navă spațială din interiorul acestui val ar putea să călărească această „warp bubble” și să atingă viteze mai mari decât viteza luminii. Aceasta este ceea ce este cunoscut sub numele de „Metoda Alcubierre”.

Interpretat în contextul Relativității generale, interiorul acestei bule warp ar constitui cadrul de referință inerțial pentru orice aflat acolo. În acest mod, astfel de bule pot apărea într-o regiune plană anterior de spațiu-timp și depășesc viteza luminii. Deoarece nava nu se deplasează prin spațiu-timp (ci în mișcare spațiul-timp în sine), efecte relativiste convenționale (cum ar fi dilatarea timpului) nu se vor aplica.

Pe scurt, metoda Alcubierre permite deplasarea FTL fără a încălca legile relativității în sens convențional. Așa cum Agnew a spus prin e-mail revistei Universe Today , el a fost inspirat de acest concept încă din liceu și îl urmărește încă de atunci:

„Am aprofundat mai mult în matematică și știință și, ca urmare, am început să mă interesez de ficțiunea științifică și de teoriile avansate la o scară mai tehnică. Am început să privesc Star Trek, serialele Original și The Next Generation și am observat cum au prezis sau au inspirat invenția telefoanelor mobile, tabletelor și alte facilități. M-am gândit la unele dintre celelalte tehnologii, cum ar fi torpilele fotonice, fazerele și unitatea warp și am încercat să cercetez atât ce trebuie să spună „star trek science”, cât și „real world science equivalent” despre asta. Apoi am dat peste dosarul original al lui Miguel Alcubierre și după ce am digerat teoria o perioadă, am început să cercetez și alte lucrări și să mă adânc în teorie. ”

În timp ce conceptul a fost respins, în general, pentru a fi în întregime teoretic și extrem de speculativ, în ultimii ani a căpătat un suflu nou în mare parte grație dr. Harold „Sonny” White și Advanced Propulsion Team Lead care este responsabilă de Laboratorul de fizică de propulsie avansată al Centrului Spațial NASA Johnson (Laboratorul Eagleworks).

În cadrul 100 Year Starship Symposium în 2011, Dr. White a împărtășit câteva calcule actualizate ale Alcubierre Metric, care au făcut obiectul unei prezentări intitulată „Warp Field Mechanics 101” (și un studiu cu același nume). Conform doctorului White, teoria lui Alcubierre a fost temeinică, dar a avut nevoie de teste și dezvoltari serioase. De atunci, el și colegii săi au făcut aceste lucruri chiar prin Eagleworks Lab.

Pe o cale similară, Agnew și-a petrecut o mare parte din cariera sa academică cercetând teoria și mecanica din spatele warp mechanics. Sub mentoratul dr. Jason Cassibry – profesor asociat de inginerie mecanică și aerospațială și membru al facultății din UAH’s Propulsion Research Center – lucrarea Agnew a culminat cu un studiu care abordează obstacolele și oportunitățile majore reprezentate de cercetările privind warp mechanics .

Așa cum a relatat Agnew, unul dintre cele mai mari obstacole este faptul că conceptul de „warp drive” nu este încă luat în serios în cercurile științifice:

„Din experiența mea, atunci când deschid vorba într-o discuție despre warp drive lumea începe să chicotească, deoarece este atât de teoretică și chiar în afara științei ficționale. De fapt, de multe ori sunt întâmpinat cu observații ostile, și este folosită ca un exemplu legat de ceva cu totul bizar, ceea ce este de înțeles. Și eu, inițial l-am grupat, mental, în aceeași categorie cu conceptele superluminice tipice, deoarece, evident, toate încalcă presupunerea că „viteza luminii este viteza supremă”. Abia până am săpat în teorie mai atent, mi-am dat seama că nu există aceste probleme. Cred că se va vedea un mai mare interes atunci când se va profita de progresele realizate. Natura istorică teoretică a ideii este, de asemenea, un factor de descurajare în sine, deoarece este mult mai dificil de observat progrese substanțiale atunci când se privesc ecuații în loc de rezultate fizice, palpabile. „

Foto-În februarie 2016, LIGO a detectat undele gravitaționale pentru prima dată. Așa cum ilustrează ilustrația acestui artist, undele gravitaționale au fost create prin contopirea găurilor negre. A treia detecție tocmai anunțată a fost creată și atunci când s-au contopit două găuri negre. Credit: LIGO / A. Simonnet.

Impresia artistului de a contopi găuri negre binare, o cauză majoră a evenimentelor gravitaționale. Credit: LIGO / A. Simonnet.

În timp ce domeniul este încă la început, au existat o serie de dezvoltări recente care au ajutat. De exemplu, descoperirea undelor gravitaționale (GWSs) realizată de LIGO scientists în 2016, care au confirmat o predicție făcută de Einstein în urmă cu un secol și dovedește că baza pentru the warp drive există în natură. După cum a indicat Agnew, aceasta este poate cea mai semnificativă dezvoltare, dar nu singura:

„În ultimii 5-10 ani, au fost multe progrese excelente în the anticipated effects of the drive , despre cum am putea să-i conferim o existență fizică, consolidarea ipotezelor și asupra conceptelor fundamentale și modalităților de testare a teoriei într-un laborator.

„Descoperirea LIGO de câțiva ani în urmă a fost, după părerea mea, un salt uriaș în față pentru știință, deoarece a demonstrat, experimental, că spațiul-timp se poate văluri „warp’”și se poate îndoi în prezența unor câmpuri gravitaționale enorme, iar acest lucru este propagat în tot universul într-un mod pe care îl putem măsura. Înainte, se credea că acesta ar fi probabil, datorită lui Einstein, dar acum o știm sigur. ”

Având în vedere că sistemul se bazează pe extinderea și compresia spațiului, a spus Agnew, această descoperire a demonstrat că unele dintre aceste efecte apar în mod natural. „Acum că știm că efectul este real, următoarea întrebare, în mintea mea, este:„ cum o studiem și cum o putem genera noi în laborator? ”, A adăugat el. „Evident, ceva de genul acesta ar fi o investiție uriașă de timp și resurse, dar ar fi extraordinar de benefic.”

Desigur, conceptul Warp Drive necesită sprijin suplimentar și numeroase progrese înainte ca cercetările experimentale să fie posibile. Acestea includ pași înainte în ceea ce privește cadrul teoretic, precum și în cel tehnologic.

„În esență, ceea ce este necesar pentru o unitate warp este o modalitate de a extinde și de a contracta spațiu-timp într-un mod local, cum ar fi în jurul unui obiect mic sau navă. Știm sigur că densități energetice foarte mari, sub formă de câmpuri EM sau de masă, de exemplu, pot provoca curbură în spațiu. Costurile, conform unor calcule preliminare, vor fi foarte mari ”

„Pe de altă parte, the technical areas ar trebui să încerce să perfecționeze echipamentul și să proceseze cât mai mult posibil, ceea ce face ca obținerea acestei densități energetice să devină mai plauzibilă. Cred că există o șansă ca, odată ce efectul va putea fi duplicat la o scară de laborator, acesta va duce la o înțelegere mult mai profundă a modului în care funcționează gravitația și poate deschide ușa unor noi teorii. Presupun că, rezumând, cel mai mare obstacol este energia și, prin aceasta, vin obstacole tehnologice, având nevoie de câmpuri EM mai mari, echipamente mai sensibile, etc. ”

Cantitatea pură de energie pozitivă și negativă necesară pentru a crea o bulă warp rămâne cea mai mare provocare asociată conceptului lui Alcubierre. În prezent, oamenii de știință consideră că singura cale de a menține densitatea de energie necesară pentru producerea bulei este cu ajutorul materiei exotice. Oamenii de știință estimează, de asemenea, că necesarul total de energie ar fi echivalent cu masa de Jupiter.

Totuși, acest lucru reprezintă o scădere semnificativă față de estimările energetice anterioare, care au susținut că ar avea nevoie de o masă energetică echivalentă cu întregul Univers. Cu toate acestea, o cantitate de materie exotică cât Jupiter este încă prohibitiv de mare. În acest sens, mai sunt necesare progrese semnificative pentru a reduce cerințele energetice la ceva mai realist.

Unicul mod previzibil de a face acest lucru este prin avansări suplimentare în fizica cuantică, mecanica cuantică și metamateriale, spune Agnew. În ceea ce privește latura tehnică a lucrurilor, va fi nevoie de progrese suplimentare în crearea de superconductori, interferometre și generatoare magnetice. Și, desigur, există problema finanțării, care este întotdeauna o provocare atunci când vine vorba de concepte care sunt considerate „out there”.

Dar, după cum afirmă Agnew, aceasta nu este o provocare insurmontabilă. Având în vedere progresele înregistrate până acum, există motive de a fi optimiști în ceea ce privește viitorul:

„Teoria a arătat până acum că scopul merită urmărit și este mai ușor acum decât înainte de a oferi dovezi legitime. În ceea ce privește justificările pentru alocarea resurselor, posibilitatea de a explora mai departe de sistemul nostru solar, chiar dincolo de galaxia noastră, ar fi un salt enorm pentru omenire. Și avansul tehnologic rezultat din împingerea la extrem a cercetărilor ar fi cu siguranță benefic. ”

La fel ca avionica, cercetarea nucleară, explorarea spațiului, mașinile electrice și rachetele reutilizabile, Alcubierre Warp Drive pare destinat să fie unul dintre acele concepte care vor trebui să se lupte cu inerția. Dar, ca și în alte cazuri istorice, în cele din urmă se ajunge la un punct de unde devine vizibilă luminița de la capătul tunelului, iar întoarcerea nu mai este posibilă!

Și având în vedere preocuparea noastră din ce în ce mai mare pentru exoplanete (un alt domeniu exploziv al astronomiei), nu lipsesc oamenii care speră să trimită misiuni către stele din apropiere pentru a căuta planete potențial locuibile. Și, după cum arată exemplele menționate, cu siguranță, all that’s needed to get the ball rolling is a good push…

***

Proză SF — ALTERA PARS

MARȚIENII DIN INSULA COMORII„…Poți să-mi spui Harry. Am terminat Universitatea din Berkeley și am devenit ziarist la San Fancisco Chronicle. Probabil cunoști ziarul nostru, care a avut o contribuție importantă în perioada Beat Generation și Hippie. Denumirea de beatnik a fost inventată de Herb Caen în redacția ziarului nostru în 1958 (eram puști pe atunci), […]