The Antarctic ozone hole hit its smallest annual peak on record since tracking began in 1982, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) and NASA announced Monday. Although we’re making progress in cutting down on the use of ozone-depleting chemicals, the milestone doesn’t mean we’ve solved the problem, the agencies cautioned.

Instead, scientists attribute the relatively tiny ozone hole to unusually mild temperatures in that layer of the atmosphere.

According to NASA and the NOAA, the annual ozone hole – which consists of an area of heavily depleted ozone high in the stratosphere above Antarctica, between 7 and 25 miles (11 and 40 kilometres) above the surface – reached its peak extent of 6.3 million square miles on September 8 and then shrank to less than 3.9 million square miles during the rest of September and October.

„During years with normal weather conditions, the ozone hole typically grows to a maximum of about 8 million square miles,” the agencies said in a news release.

This is the third time in 40 years that weather systems have caused warm stratospheric temperatures that put the brakes on ozone loss, the federal science agencies said. Similar weather patterns led to unusually small ozone holes in 1988 and 2002, they reported.

„It’s a rare event that we’re still trying to understand,” Susan Strahan, an atmospheric scientist at the NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center in Maryland, said in a news release.

„If the warming hadn’t happened, we’d likely be looking at a much more typical ozone hole.”

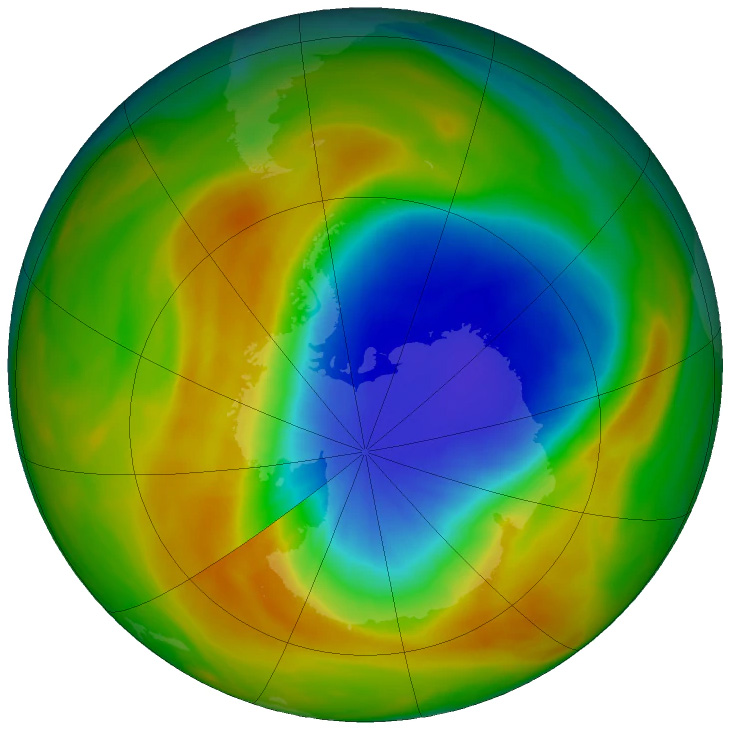

(NASA)

(NASA)

Above: A false-color view of total ozone over the Antarctic pole. The purple and blue colors are where there is the least ozone, and the yellows and reds are where there is more ozone.

The stratospheric ozone layer helps deflect incoming ultraviolet radiation from the sun, shielding life on Earth from its harmful effects, such as skin cancer, cataracts and damage to plants.

However, chemicals used for refrigeration purposes, such as chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs) and hydrofluorocarbons (HFCs), break down stratospheric ozone molecules, thereby exposing the planet’s surface to greater amounts of UV radiation.

The Montreal Protocol, a landmark international environmental treaty that took effect in 1988, has reduced CFC emissions worldwide.

These chemicals have an atmospheric lifetime of several decades and can destroy extraordinary amounts of ozone over that time. The ozone layer has been slowly but steadily recovering since the Montreal Protocol took effect, but it still has a long way to go.

Each year, an ozone hole forms during the Southern Hemisphere’s late winter as the sun’s rays initiate chemical reactions between the ozone molecules and man-made chemically active forms of chlorine and bromine.

These chemical reactions are maximized on the surface of high-flying clouds, but milder-than-average conditions in the stratosphere above Antarctica this year inhibited cloud formation and persistence, according to a NASA statement. This helped prevent the loss of a considerable amount of ozone.

For example, unlike what typically happens, there was no area above Antarctica this year that was completely lacking in ozone, according to measurements from NOAA using weather balloons.

The weather systems that minimized ozone depletion in September, known as „sudden stratospheric warming” events, were unusually strong this year. About 12 miles (19 kilometres) above Earth’s surface, temperatures during September were 29 degrees higher than average, NASA reported, „which was the warmest in the 40-year historical record for September by a wide margin.”

As can occur with stratospheric warming events in the Northern Hemisphere, this weather event helped to weaken the Antarctic polar vortex, a ribbon of high-speed air encircling the South Pole that typically concentrates the coldest air near or over the pole itself.

Instead, the Antarctic polar vortex was knocked off balance and slowed significantly, from an average wind speed of 161 mph (260 km/h) to just 67 mph (107 km/h).

The slowing vortex allowed air to sink in the lower stratosphere, where it warmed and inhibited cloud formation. In addition, the reconfigured weather map helped to import ozone-rich air from other parts of the Southern Hemisphere, rather than sealing off the polar region entirely. This also helped boost ozone levels there.

Interestingly, climate change isn’t expected to cause more frequent sudden stratospheric warming events over the South Pole, and instead it could strengthen, not weaken, the polar vortex overall.

In contrast with global warming, the discovery of the ozone hole by scientists at the British Antarctic Survey in 1985 galvanized international action. This swiftly resulted in a binding international treaty that many experts consider the most successful environmental agreement to date.

In fact, policymakers are even using it to address HFCs, ozone-depleting chemicals that are also global-warming pollutants.

Since 2000, atmospheric levels of CFCs have been slowly declining, but they are still sufficiently abundant to cause annual ozone holes at the North and South poles.

Assuming that CFC use continues at recent rates and that no ozone-depleting chemical substitutes are found and widely used, scientists anticipate the ozone hole to shrink to its 1980 size by about 2070 as CFCs still in the upper atmosphere gradually decline.

This article was originally published by The Washington Post.

Gaura de ozon din Antarctica a atins cel mai mic vârf anual de când a început urmărirea în 1982, au anunțat luni Administrația Națională Oceanică și Atmosferică (NOAA) și NASA. Deși utilizarea substanțelor chimice care sărăcesc stratul de ozon a fost drastic limitată odată cu the Montreal Protocol – the 1987 agreement to stop producing ozone depleting substances (ODSs), asta nu înseamnă că am rezolvat problema, au avertizat cele două agenții.

De fapt, oamenii de știință consideră că micșorarea relativă a găurii de ozon ar putea fi efectul temperaturilor neobișnuit de blânde din acel strat al atmosferei.

Conform NASA și NOAA, gaura de ozon – care consta într-o zonă sărăcită în ozon din stratosfera Antarcticii, între 7 și 25 de mile (11 și 40 de kilometri) deasupra solului – a atins valoarea maximă de 6,3 milioane mile pătrate pe 8 septembrie și apoi s-a redus la mai puțin de 3,9 milioane mile pătrate în restul lunii septembrie și octombrie.

„Pe parcursul anilor cu condiții meteorologice normale, gaura de ozon creștea de obicei cu un maxim de aproximativ 8 milioane de mile pătrate”, au spus agențiile într-un comunicat de presă.

Aceasta este a treia oară în 40 de ani când sistemele meteorologice au înregistrat temperaturi stratosferice ridicate care au pus frâne pierderii de ozon. Rapoartele meteorologice similare au indicat găuri de ozon neobișnuit de mici în 1988 și 2002, au raportat acestea.

„Este un eveniment rar pe care încă încercăm să-l înțelegem”, a spus Susan Strahan, meteorolog la Centrul de zbor spațial Goddard al NASA din Maryland, într-un comunicat de presă.

„Dacă încălzirea nu s-ar fi întâmplat, probabil că am privi o gaură de ozon mult mai tipică”.

Foto:

Mai sus: O vedere prelucrată a ozonului total de deasupra polului Antarctic. Culorile violet și albastru sunt acolo unde este cel mai puțin ozon, iar galbenele și roșii sunt acolo unde este mai mult ozon.

Stratul de ozon stratosferic ajută la îndepărtarea radiațiilor ultraviolete de la soare, protejând viața de pe Pământ de efectele sale dăunătoare, precum cancerul de piele, cataracta și deteriorarea plantelor.

Cu toate acestea, substanțele chimice utilizate în scopuri de refrigerare, cum ar fi clorofluorocarburi (CFC) și hidrofluorocarburi (HFC), descompun molecule de ozon stratosferice, expunând astfel suprafața planetei la cantități mai mari de radiații UV.

Protocolul de la Montreal, un tratat de mediu internațional care a intrat în vigoare în 1988, a redus emisiile de CFC la nivel mondial.

Aceste substanțe chimice au o durată de viață atmosferică de câteva decenii și pot distruge cantități extraordinare de ozon în acest timp. Stratul de ozon s-a redresat lent, dar constant, de la intrarea în vigoare a Protocolului de la Montreal, dar mai rămâne un drum lung de parcurs.

În fiecare an, o gaură de ozon se formează în zona emisferei de sud la sfârșitului iernii, în timp ce razele soarelui inițiază reacții chimice între moleculele de ozon și cele create de om, active chimic, de clor și brom.

Aceste reacții chimice sunt maximizate pe suprafața norilor de mare înălțime, dar temperaturile mai ridicate decât media din stratosfera de deasupra Antarcticii în acest an au inhibat formarea și persistența norilor, potrivit unui comunicat al NASA. Acest lucru a contribuit la prevenirea pierderii unei cantități considerabile de ozon.

De exemplu: în acest an, spre deosebire de ceea ce se întâmplă de obicei, nu a existat nicio zonă deasupra Antarcticii care să fie lipsită complet de ozon, conform măsurătorilor de la NOAA care au folosit baloane meteorologice.

Sistemele meteorologice care au minimizat epuizarea ozonului în septembrie, cunoscute sub numele de evenimente de „încălzire stratosferică bruscă”, au fost neobișnuit de puternice în acest an. La aproximativ 12 mile (19 kilometri) deasupra suprafeței Pământului, temperaturile în septembrie au fost cu 2,9 de grade mai mari decât media, a informat NASA, „care a fost luna cea mai caldă din ultimii 40 de ani record istoric pentru luna septembrie”.

Așa cum se poate întâmpla cu evenimentele de încălzire stratosferică din emisfera nordică, acest eveniment meteorologic a ajutat la slăbirea vortexului polar antarctic, o panglică de aer de mare viteză care încercuiește Polul Sud care concentrează de obicei cel mai rece aer lângă sau peste polul însuși.

În schimb, vortexul polar antarctic a fost eliminat și a încetinit semnificativ, de la o viteză medie a vântului de 161 mph (260 km / h) la doar 67 mph (107 km / h).

Aceasta a permis aerului să se scufunde în stratosfera inferioară, unde s-a încălzit și a inhibat formarea de nori. În plus, a ajutat la importul de aer bogat în ozon din alte părți ale emisferei sudice, mai degrabă decât la sigilarea completă a regiunii polare. Acest lucru a contribuit, de asemenea, la creșterea nivelului de ozon de acolo.

Este interesant faptul că, deși schimbările climatice era de așteptat să provoace evenimente de încălzire stratosferică bruscă peste Polul Sud, specialiștii presupuneau că ele să consolideze, nu să slăbească, vortexul polar.

Spre deosebire de încălzirea globală, descoperirea găurii de ozon de către oamenii de știință de la British Antarctic Survey din 1985 a galvanizat acțiunea internațională. Acest lucru a dus rapid la un tratat internațional obligatoriu pe care mulți experți îl consideră cel mai de succes acord de mediu de până în prezent.

De fapt, factorii de decizie îl folosesc chiar și pentru a aborda HFC-urile, substanțe care consumă ozon, care sunt, de asemenea, poluanți cu efect de încălzire globală.

Începând cu anul 2000, nivelurile atmosferice ale CFC-urilor au scăzut lent, dar sunt încă suficient de abundente pentru a provoca găuri de ozon anuale la polul Nord și Sud.

Presupunând că utilizarea CFC va continua la ritmurile actuale și că nu se găsesc și utilizează pe scară largă alți înlocuitori chimici care sărăcesc ozonul, oamenii de știință anticipează că gaura de ozon o să se micșoreze până la dimensiunea sa din 1980, deoarece CFC-urile aflate încă în atmosfera superioară scad treptat.