About three and a half million years ago, the center of our galaxy exploded.

This is no exaggeration, no attempt to overstate for effect. There’s no need. The event was colossal. The explosive power coming from the core of the Milky Way easily, vastly outshone all the stars in the galaxy combined, sending two huge beams of super-high energy marching out into space in opposite directions. The scale of this event is nearly incomprehensible, and it lasted for 300,000 years.

For this time, our galaxy was a quasar, one of the most luminous objects in the Universe.

This occurrence of this event has been suspected for years, but new evidence makes the case far more compelling.

The two obvious questions are: Why did this happen, and how do we know?

[Note: I know events like this can scare some people — the psychological term is cosmophobia, a fear of things that happen in space. It’s a very real mental state, and I get nervous emails from a few folks when I write on topics like these. Let me assure you, this event cannot hurt us here on Earth, for reasons I’ll make clear below. Even if it were to happen again (unlikely for millions of years) we’re safe. I hope that helps.]

Let’s take the latter one first. What evidence do we have that this happened?

In 2003, observations using the X-ray satellite ROSAT found a lot of high-energy emission coming from the area of the sky surrounding the center of the Milky Way galaxy. It was seen at other wavelengths of light as well, and then in 2010 observations from the gamma-ray satellite Fermi were used to make an image of the super-high-energy light coming from the sky, and mapped out two huge lobes of emission centered smack dab on the galactic center.

Arguments went back and forth on what could be causing these huge bubbles of energy. I even wrote about them when it looked like the culprit was incredibly vigorous star formation, with the most massive stars blasting out energy being the engines behind the expansion. But over the years more evidence has come in, and it looks like this cannot be the explanation; the energy emitted by stars is too weak by a factor of 100 – 400 to power the events seen.

Moreover (and this is what the new research shows), there is a stream of gas circling outside the Milky Way at a distance of roughly 200,000 light years. This is called the Magellanic Stream and it stretches across over half the sky! The gas comes from two small satellite galaxies to the Milky Way called the Small and Large Magellanic Clouds called the SMC and LMC for short). These two galaxies are interacting with each other gravitationally, with the bigger one pulling gas out of the smaller one, and that gas gets left behind like a contrail as they move through space. The stream isn’t terribly dense, but it’s very long and quite massive, with a mass of something like 2 billion times that of the Sun.

It glows very faintly; the hydrogen in it emits a kind of light called H-alpha (which is in the red part of the spectrum, and is responsible for making nebulae glow so gloriously red). There are three hot spots, though, where the gas glows more brightly. One is centered on the LMC, which isn’t too surprising, but the other two are far off in space from either galaxy. It turns out, though, that these spots are right over the north and south poles of our galaxy. Literally, straight up and down from the center of the Milky Way, perpendicular to its flat disk.

These spots are where the light from the event that occurred lit up the gas in the stream. From the amount of energy emitted, it looks like it was struck by the beam of light about 3.5 million years ago.

Remember, this gas is 200,000 light years away! That’s an incredible distance. What sort of event could possibly emit that kind of energy? What could power it?

There’s now only one main suspect: Sgr A* (literally, „Sagittarius A star”), the supermassive black hole lying right at the heart of the Milky Way.

This black hole is huge, with over 4 million times the mass of the Sun. It grew as the Milky Way itself formed, and the two are inexorably linked in many ways. When our galaxy was young, gas was far more abundant, and material would fall into the grip of the black hole. As it did it piled up in a disk around it, called an accretion disk. Matter close to the black hole whipped around it at nearly the speed of light, while material farther out moved more slowly. This generated incredible amounts of friction, heating the disk up to millions of degrees. It blasted out energy, ironically making it one of the brightest objects in the Universe even though it was powered by the darkest. The energy escaped in beams like those of a lighthouse, emitted perpendicular to the accretion disk, up and down out of the galaxy.

We call objects like these active galaxies. They were common when the Universe was young, though far more rare now.

But… our black hole isn’t feeding now. It’s not glowing, so it’s called quiescent. If that’s the case, how could it have erupted 3.5 million years ago?

A key piece of evidence is the existence of a ring of very young stars orbiting very close to Sgr A*. These stars are only 4–6 million old, and orbit just a little over 3 light years from the beast (for comparison, the nearest star system to the Sun is Alpha Centauri, which is over 4 light years away). Stars like this form from huge gas clouds, so the stars being there at all strongly implies there was a lot of gas there as well. At that distance, gas clouds could easily be torn apart by the black hole’s gravity and dropped down into its waiting maw. This would form an accretion disk, and that was what could have powered the huge explosion. The amount of gas wasn’t nearly as much as when the galaxy was young, so it was a temporary rekindling of our galactic quasar; the event lasted only 300,000 years, not millions or even billions as it did when the galaxy was young.

The energy from this event is what pumped up the gas bubbles seen by ROSAT and Fermi and so many other observatories, and the flash of light is what lit up the Magellanic Stream in two spots, the gas directly in the path of those beams of energy.

While the picture is not yet complete, the new research makes a pretty good case that this is what happened.

There is also a third question to add to the previous two: Will this happen again? Well, yes. It almost certainly will. The good news there is that the time between these events is very long on human scales, millions of years. On average, a given galaxy will undergo an event like this every ten million years or so*. That’s not a schedule, it’s not clockwork. It might happen sooner, or later. Either way it’s likely millions of years between events, so we’re OK there. From what we can tell there’s nowhere near enough gas close to the galactic center to start something like this up again.

Also, these beams aren’t pointed anywhere near us, so we’re almost certainly going to be unaffected by them. And even if they were pointed into the galactic disk instead of up and out away from it, there’s a huge amount of material between us and the galactic center, 26,000 light years away. We’re safe.

After all, this last event was 3 million years ago, yet here we are. There’s no evidence at all our planet was affected by this in the slightest.

I personally find all this fascinating. Disparate observations by vastly different observatories all find different aspects of this event, and astronomers have had to piece the evidence together to figure out what’s going on. Now we have a coherent picture of it, a singular and ridiculously powerful event that occurred long ago, and may yet occur again. And all of this tells us so much about the history of our galaxy, the different parts that make it up, and even material that lies far outside our galaxy as a trail of stardust in the sky.

În urmă cu aproximativ trei milioane și jumătate de ani, centrul galaxiei noastre a explodat.

Aceasta nu este o exagerare, nici o încercare de a supraestima efectul. Nu e nevoie. Evenimentul a fost colosal. Puterea explozivă provenind din nucleul Căii Lactee cu ușurință a strălucit cam cât toate stelele din galaxie combinate, trimițând două fascicule uriașe de energie super-înaltă care se îndreptau spre spațiu în direcții opuse. Amploarea acestui eveniment este aproape incoprehensibilă și a durat 300.000 de ani.

Atunci, galaxia noastră a fost un quasar, unul dintre cele mai luminoase obiecte din Univers.

Existența acestui eveniment a fost suspectată de ani de zile, dar noile dovezi apărute fac cazul să fie mult mai convingător.

Cele două întrebări evidente sunt: de ce s-a întâmplat acest lucru și cum l-am aflat?

Notă: Știu că astfel de evenimente pot speria unii oameni – termenul psihologic este cosmofobie, o frică de lucruri care se întâmplă în spațiu. Este o stare mentală foarte reală și primesc e-mailuri nervoase de la unii oameni atunci când scriu despre subiecte ca acestea. Permiteți-mi să vă asigur că acest eveniment nu ne poate răni aici pe Pământ, din motive pe care le voi clarifica mai jos. Chiar dacă s-ar întâmpla din nou (puțin probabil de acum în câteva milioane de ani), deocamdată suntem în siguranță. Sper că asta va ajuta…

Ce dovezi avem că s-a întâmplat asta?

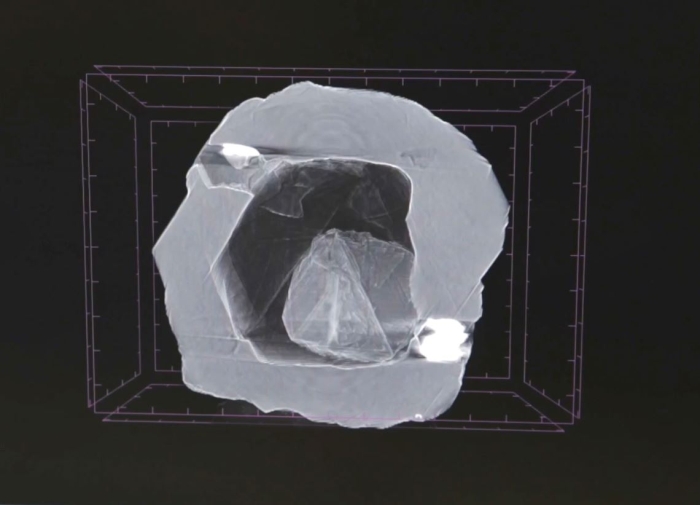

Foto 1- Două erupții uriașe de material ce se scurg din Calea Lactee, au fost văzute în razele gamma de telescopul spațial Fermi. Credit: Ettore Carretti, CSIRO (imagine radio); Echipa de sondaj S-PASS (date radio); Axel Mellinger, Universitatea Central Michigan (imagine optică);

În 2003, observațiile folosind satelitul cu raze X ROSAT au descoperit o mulțime de emisii cu energie mare provenind din zona cerului care înconjoară centrul galaxiei Calea Lactee. De asemenea, a fost văzută și la alte lungimi de undă ale luminii, iar apoi în 2010, observațiile satelitului cu raze gamma Fermi au fost folosite pentru a face o imagine a luminii de super-înaltă energie și s-au trasat doi lobi uriași de emisie.

Argumentele cu privire la ceea ce ar putea provoca aceste bule uriașe de energie erau împărțite. Am scris chiar eu despre ele atunci pe când se părea că vinovatul a fost o formare de stele incredibil de viguroasă, cele mai masive stele fiind motoarele energetice din spatele expansiunii. Dar de-a lungul anilor au apărut mai multe dovezi și se pare că nu aceasta ar fi explicația; energia emisă de stele fiind prea slabă la un factor de 100 / 400 pentru a alimenta evenimentele văzute.

Mai mult decât atât (și asta arată noua cercetare), există un flux de gaz care se înfășoară în afara Căii Lactee la o distanță de aproximativ 200.000 de ani-lumină. Acesta se numește Pârâul Magellanic și se întinde peste mai bine de jumătate din cer! Gazul provine de la două galaxii satelite mici la Calea Lactee numite micii și marii nori magellanici, SMC și LMC mai pe scurt). Aceste două galaxii interacționează gravitațional între ele, cu cea mai mare care scoate gazul din cea mai mică și gazul acesta rămâne în urmă ca un contrail în timp ce galaxiile se deplasează prin spațiu. Curentul nu este teribil de dens, dar este foarte lung și destul de masiv, cu o masă de aproximativ 2 miliarde de ori mai mare decât cea a Soarelui.

Straluceste foarte slab; hidrogenul din el emite un fel de lumină numită H-alfa (care se află în partea roșie a spectrului și este responsabilă pentru a face ca nebuloasele să strălucească atât de roșu). Există totuși trei puncte fierbinți, unde gazul strălucește mai puternic. Unul este centrat pe LMC, ceea ce nu este prea surprinzător, dar celelalte două sunt mai departe în spațiu față de oricare dintre aceste galaxii. Totuși, se dovedește că aceste locuri sunt chiar la polul nord și sud al galaxiei noastre. Literal, drept în sus și în jos din centrul Căii Lactee, perpendicular pe discul său plat.

Acestea sunt zonele în care emisia de la evenimentul care a avut loc a aprins gazul din curent. Din cantitatea de energie emisă, se pare că asta s-a întâmplat în urmă cu aproximativ 3,5 milioane de ani.

Nu uitați, acest gaz este la o distanță de 200.000 de ani lumină de noi! Aceasta este o distanță incredibilă. Ce fel de eveniment ar putea emite acest tip de energie? Ce l-ar putea alimenta?

Acum există un singur suspect principal: Sgr A * (literalmente, „Sagittarius A star”), gaura neagră supermasivă situată chiar în inima Căii Lactee.

Această gaură neagră este uriașă, de peste 4 milioane de ori masa Soarelui. A crescut pe măsură ce Calea Lactee însuși s-a format, iar cele două sunt legate inexorabil în multe feluri. Când galaxia noastră era tânără, gazul era mult mai abundent, iar materialul cădea în strânsoarea găurii negre. Așa cum a făcut-o într-un disc în jurul găurii negre, numit disc de acreție. Gazul era absorbit aproape la viteza luminii, în timp ce materialul acreționar se mișca mai încet. Acest lucru a generat cantități incredibile de frecare, încălzind discul până la milioane de grade până când energia a izbucnit , făcându-l ironic să fie unul dintre cele mai strălucitoare obiecte din Univers, chiar dacă a fost alimentat de cea mai întunecată. Energia scăpa în fascicule precum cele ale unui far, emise perpendicular pe discul de acumulare, în sus și în jos în afara galaxiei.

Numim obiecte ca aceste galaxii active. Erau obișnuite când Universul era tânăr, deși acum sunt mult mai rare.

Foto – Desen artistic al unui blazar, o galaxie cu o gaură neagră super-masivă care emană energie. Credit: DESY, Science Communication LabZoom In

Dar… gaura noastră neagră nu se mai hrănește acum. Nu este strălucitoare, așa că se numește quiescent. Dacă acesta este situația, cum ar fi putut să izbucnească acum 3,5 milioane de ani?

O dovadă cheie este existența unui inel de stele foarte tinere care orbitează foarte aproape de Sgr A *. Aceste stele au doar 4–6 milioane de ani și orbitează la mai puțin de 3 ani-lumină față de bestie (pentru comparație, cel mai apropiat sistem stelar de Soare este Alpha Centauri, care se află la peste 4 ani lumină). Dar aceste stele s-au născut din nori uriași de gaz. La acea distanță, norii de gaz puteau fi ușor desprinși de gravitația găurii negre și ar forma un disc de acumulare iar asta ar fi putut alimenta explozia uriașă. Cantitatea de gaz nu a fost aproape la fel ca atunci când galaxia era tânără, deci a fost o refacere temporară a qasarului nostru galactic; evenimentul a durat doar 300.000 de ani, nu milioane sau chiar miliarde așa cum s-a întâmplat atunci când galaxia era tânără.

Energia de la acest eveniment este cea care a pompat bulele de gaz văzute de ROSAT și Fermi și atâtea alte observatoare, iar flash-ul de lumină este ceea ce a luminat fluxul Magellanic în două puncte, gazul direct pe calea acelor fascicule de energie .

Imaginea nu este încă completă, dar noua cercetare oferă suficiente indicații că evenimentul a avut loc în acest mod.

Există, de asemenea, o a treia întrebare de adăugat la cele două precedente: Se va întâmpla asta din nou? Ei bine, da. Aproape sigur o va face. Vestea bună este că timpul dintre aceste evenimente este foarte lung la scară umană, milioane de ani. În medie, o anumită galaxie va suferi un eveniment ca acesta la fiecare zece milioane de ani sau cam așa ceva. S-ar putea întâmpla mai devreme sau mai târziu. Oricum ar fi probabil milioane de ani între evenimente, așa că suntem bine aici. Din ceea ce putem spune nu există suficient gaz aproape de centrul galactic pentru a începe din nou ceva de genul acesta.

De asemenea, aceste fascicule nu sunt orientate către noi, așa că aproape sigur nu vom fi afectate de ele. Și chiar dacă au fi fost îndreptate în discul galactic în loc să fie în sus și în afara acestuia, există o cantitate imensă de material între noi și centrul galactic, aflat la 26.000 de ani lumină. Suntem în siguranță.

La urma urmei, acest ultim eveniment a fost acum 3 milioane de ani, totuși suntem aici. Nu există dovezi deloc că planeta noastră a fost afectată în cele mai mici cazuri.

Personal găsesc toate acestea fascinante. Acum avem o imagine coerentă a acestui eveniment singular și extraordinar de puternic, care a avut loc cu mult timp în urmă, și poate să apară încă o dată. Și toate acestea ne povestesc atât de multe despre istoria galaxiei noastre, despre diferitele părți care o alcătuiesc și chiar despre materialul care se află departe de galaxia noastră, ca o urmă de praf ceresc pe cer.

***